PLA reform and China´s strategy: A short review

The Chinese government is working to make its military stronger, more efficient, and more technologically advanced to become a top-tier force within thirty years. With a budget that has soared over the past decade, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) already ranks among the world’s leading militaries in areas including artificial intelligence and anti-ship ballistic missiles.

Experts warn that as China’s military modernizes, it could become more assertive in the Asia-Pacific region by intensifying pressure on Taiwan and continuing to militarize disputed islands in the East and South China Seas. U.S. President Donald J. Trump’s administration believes China is a great-power rival, though the PLA still has a way to go before it can challenge the United States, experts say.

The modern Chinese military got its start during the civil war (1927–1949) between CCP forces and nationalist Kuomintang forces. The guerrilla-style army relied on a mass mobilization of Chinese citizens, and the PLA largely preserved this organizational structure in the following decades to protect its borders.

A turning point came in the 1990s, when the CCP witnessed two demonstrations of U.S. military power in its hemisphere: the Gulf War and the Taiwan Strait Crisis. Struck by the sophistication of U.S. forces, Chinese leaders acknowledged that it lacked the technology to wage a modern war and prevent foreign powers from intervening in the region. Officials launched an effort to catch up to top-tier militaries by increasing defense spending, investing in new weapons to enhance anti-access area denial (A2/AD), and establishing programs to boost the Chinese defense industry.

Another shift began in 2012, when President Xi Jinping came to power. Championing what he calls the Chinese Dream, a vision to restore China’s great-power status, Xi has gone further to push military reforms than his predecessors. Xi leads the Central Military Commission, the PLA’s highest decision-making body, and he has committed to producing a “world class force” that can dominate the Asia-Pacific and “fight and win” global wars by 2049.

The Chinese military faces big, structural changes. Among his most significant reforms are new joint theater commands, deep personnel cuts, and improvements to military-civilian collaboration. He is pushing to transform the PLA from a largely territorial force into a major maritime power.

Army. The army is the largest service and was long considered the most important, but its prominence has waned as Beijing seeks to develop an integrated fighting force with first-rate naval and air capabilities. As the other services expanded, the army shrunk to around 975,000 troops, according to the Internationalö Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). Reforms have focused on streamlining its top-heavy command structure; creating smaller, more agile units; and empowering lower-level commanders. The army is also upgrading its weapons. Its lightweight Type 15-tank, for example, came into service in 2018 and allows for engagement in high-altitude areas, such as Tibet.

Navy. The navy has expanded at an impressive rate to become the world’s largest naval force in terms of ship numbers. In 2016, it commissioned 18 ships, while the U.S. Navy commissioned five. The PLA’s ship quality has also improved: RAND Corporation found that more than 70% of the fleet could be considered modern in 2017, up from less than 50 percent in 2010.

Experts say the navy, which has an estimated 250,000 active service members, has become the dominant force in China’s near seas and is conducting more operations at greater distances. Its modernization priorities include commissioning more nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers. China has two aircraft carriers, compared to the United States’ eleven. A third carrier, which is being built domestically, is expected to be operational by 2022.

Air Force. The air force has also grown, with 395,000 active service members in 2018. It has acquired advanced equipment, some thought to becopierd from stole US designs, including airborne warning and control systems, bombers, and unmanned aerial vehicles. The air force also has a collection of stealth aircraft, including-20 fighters. In 2015, RAND Corporation estimated that half of China’s fighters and fighter-bombers were modern.

Rocket Force. Responsible for maintainingChina´s conventional and nuclear missiles, the rocket force was elevated to an independent service during reforms in 2015. It has around 120,000 active troops. China has steadily increased its nuclear arsenal—it had an estimated in 2019—and modernized its capabilities, including the development of 290 warheadsanti-ship ballistic missiles that could target U.S. warships in the Western Pacific, as part of its A2/AD strategy. China reportedly has the most midrange ballistic and cruise missiles, weapons that until recently the United States and Russia were prohibited from producing.

The PLA is also developing hypersonic missiles, which can travel many times faster than the speed of sound and are therefore more difficult for adversaries to defend against. While Russia is the only country with a deployed hypersonic weapon, China’s medium-range DF-17 missile is expected to be operational in 2020. The Pentagon has said it will likely be several years before the United States has one.

Strategic Support Force. Established during the 2015 reforms, the Strategic Support Force manages the PLA’s electronic warfare, cyberwarfare, and psychological operations, among other high-tech missions. With an estimated 145,000 service members, it is also responsible for the military’s space operations, including those with satellites.

On the RANDblog experts predicted resistance of parts of the military against the PLA reforms in the contribution: “People’s Liberation Army Reforms and Their Ramifications”from 2018:

“At the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee in November 2013, the Communist Party of China formally announced a series of major reforms[1] to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). So far, those reforms have included a reduction of 300,000 personnel, a reorganization of the former seven Military Regions into five “theater commands,” and the restructuring of the former four General Departments into 15 smaller organizations that all report directly to the Central Military Commission (CMC). Official media coverage has also detailed an extensive anti-corruption campaign that has led to disciplinary action against dozens of high-ranking PLA officers, as well as plans for an end to fee-based services that had been run by PLA personnel as secondary sources of income.

This newest round of reforms has been portrayed as a far-reaching process for both the PLA and Chinese society as a whole. It is expected to last until 2020, and will improve the military’s efficiency, warfighting capability, and—most importantly, from the Party’s perspective—its political loyalty. However, the reforms also challenge entrenched interests within the PLA, and could lead to reluctance within the military to adjust to new realities. Nevertheless, the reforms will likely succeed due both to recognition within the PLA of continued weakness in operational capabilities and to the senior Party leadership’s ability to co-opt support from various groups within the institution.

https://www.rand.org/blog/2016/09/pla-reforms-and-their-ramifications.html

.Xi Jinping has now made this a top priority, became chief of the Central Military Commission , deposed several generals and officers such as highranking general Guo Boxiong, who were openly criticized not only for corruption, but for undermining the party line of national rejunevation and supporting the Chinese Dream inadequately. Another challenge has been corruption and what Chinese leaders perceive as weakening loyalty to the CCP. During Xi’s first six years in office, as part of a wider anticorruption campaign, he oversaw the punishment of more than thirteen thousand PLA officers, including one hundred generals, for giving and accepting bribes, according to the U.S. Department of Defense.

Acknowledging in its 2019 defense white paper that the PLA “still lags far behind the world’s leading militaries,” the Chinese government believes it must invest more in new technologies and improve logistics. But many analysts say the military’s main challenge is personnel, in that it has struggled to recruit, train, and retain a professional fighting force. “The skills are the most difficult things to teach and teach quickly,” says IISS’s Meia Nouwens. “And with the Chinese military, the scale is enormous.”

Part of this stems from a lack of experience: the PLA hasn’t fought a major military conflict in the forty years since it invaded Vietnam (it had a brief confrontation with Vietnam in 1988). Additionally, some experts have found that recent reforms have increased pressure and stress on service members.

In the Jamestown Foundation´s contribution A New Step Forward in PLA Professionalization”( China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 5) Joel Wuthnow and Phillip C. Saunders analyze the new rank-centric system of the PLA reform:

“A linchpin of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)’s transformation into a “world-class military” is whether it can recruit, cultivate, and retain talent, especially among the officer corps tasked with planning and conducting future wars. Uneven progress over the past few decades has meant that deeper reforms to the officer system are necessary under the leadership of Central Military Commission (CMC) Chairman Xi Jinping (习近平). New regulations announced in January 2021 suggest a commitment to clarifying hierarchical relationships between officers, improving the officer management system, incentivizing high performers, and recruiting and retaining officers with the right skills. Nonetheless, several challenges and complications remain.

Background

The new regulations are the latest step in a long but uneven path towards professionalization. The process began in the 1950s under then-Defense Minister Peng Dehuai (彭德怀) but was suspended just prior to the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), during which the PLA focused more on political indoctrination than developing professional skills, and even abandoned formal ranks for a time. Officer ranks were not restored until the issuance of the Active Duty Officer Law in 1988 (Xinhua, May 12, 2014), itself part of a larger effort under then-paramount leader Deng Xiaoping (邓小平) to professionalize the personnel system through formal rules and policies. Under the leadership of former CMC chairmen Jiang Zemin (江泽民)(1989-2004) and Hu Jintao (胡锦涛) (2004-2012), the PLA made further changes to recruitment and retention policies, military training and education, pay and welfare, and related areas, to promote the army’s evolving focus on fighting and winning “high-tech local wars.”(高技术局部战争, gaojishu jubu zhanzheng)[1]

Those earlier steps were apparently unsatisfactory. PLA commentary over the last decade has frequently criticized officers as mentally and professionally ill-equipped to handle the demands of modern war.[2] Moreover, corruption flourished in the PLA during the Hu period, with widespread bribery for promotions and assignments to senior positions.[3] As early as October 2013, the Third Plenum of the 18th Party Committee referenced the need to “build a system of officer professionalization” (Xinhua, November 12, 2013). The CMC endorsed this focus on revising the officer system in the general PLA-wide reform plan issued in November 2015 (Xinhua, November 26, 2015). Those changes are now part of the final phase of regulation and policy reforms, following earlier changes to the command structure, force composition (including culling thousands of non-combat-focused officers from the ranks), and training and education systems.[4] Officer system reforms also followed changes to other parts of the PLA workforce, including conscripts, NCOs, and civilians.[5]

An early clue on how the officer system might evolve came in late 2016, when former CMC Political Work Department director Zhang Yang (张阳) stated that “building a new officer management system based on military rank” is an “inevitable choice…for modern military construction” (Xinhua, December 20, 2016). Since the 2015 reforms prioritized larger structural changes to the PLA, in-depth consideration of officer system reforms did not begin until 2019 (PLA Daily, January 9). On January 1, 2021, the CMC promulgated a series of “one basic and eight supporting” regulations (法规 fagui). The former “lays the foundation for the officer system,” while the latter detail changes to specific areas such as promotion, appointments, education, assessments, pay, and retirement (PLA Daily, January 9). Beijing has not released the full text of the new regulations but remarks by a PLA spokesman and commentary have yielded some potential insights.

Moving Towards a “Rank-Centric” System

The major change involves moving to an officer hierarchy centered primarily on rank rather than grade. Understanding this change requires a short primer on the hierarchy of PLA officers. In the Chinese system, PLA officers possess both one of 10 ranks (军衔 junxian) and one of 15 grades based on position (职务等级 zhiwu dengji) (see table for details).[6] An officer’s grade was more important than rank as a determinant of his or her authority, as well as status, pay, and benefits. The grade-centric system was based on PLA ground force structure, with every PLA organization having a grade corresponding to its position in the organizational hierarchy, and officers in turn having a grade based on their positions in their organization.

Because of the lack of a commensurate number of ranks and grades and misaligned promotion cycles—officers typically receive a rank promotion every four years and a grade promotion every three years—officers at a given grade might have different ranks and vice versa. This led to confusing situations in which lower-ranked officers with high grades sometimes effectively outranked higher-ranked officers with low grades.”

https://jamestown.org/program/a-new-step-forward-in-pla-professionalization/

Table: PLA’s 15-grade and 10-rank Structure, 1988-2020

| Grade | Primary Rank | Secondary Rank |

| CMC Chairman (军委主席 junwei zhuxi) Vice Chairmen (军委副主席 junwei fu zhuxi) | N/A GEN (上将 shangjiang) | N/A |

| CMC Member (军委委员 junwei weiyuan) | GEN (上将shangjiang) | |

| TC Leader (正战区职 zheng zhan quzhi) Former MR Leader (正大军区职 zhengda jun quzhi) | GEN (上将shangjiang) | LTG (中将 zhongjiang) |

| TC Deputy Leader (副战区职 fu zhanqu zhi) Former MR Deputy Leader (副大军区职 fuda jun quzhi) | LTG (中将zhongjiang) | MG (少将 shaojiang) |

| Corps Leader (正军职 zheng jun zhi) | MG (少将shaojiang) | LTG (中将zhongjiang) |

| Corps Deputy Leader (副军职 fu jun zhi) | MG (少将shaojiang) | SCOL (大校 daxiao) |

| Division Leader (正师职 zheng shi zhi) | SCOL (大校daxiao) | MG (少将shaojiang) |

| Division Deputy Leader (副师职 fu shi zhi) / (Brigade Leader) | COL (上校 shangxiao) | SCOL (大校 daxiao) |

| Regiment Leader (正团职 zheng tuan zhi) / (Brigade Deputy Leader) | COL (上校shangxiao) | LTC (中校 zhongxiao) |

| Regiment Deputy Leader (副团职 fu tuan zhi) | LTC (中校 zhongxiao) | MAJ (少校 shaoxiao) |

| Battalion Leader (正营职 zheng ying zhi) | MAJ (少校 shaoxiao) | LTC (中校 zhongxiao) |

| Battalion Deputy Leader (副营职 fu ying zhi) | CPT (上尉 shangwei) | MAJ (少校shaoxiao) |

| Company Leader (正连职 zheng lian zhi) | CPT (上尉shangwei) | 1LT (中尉 zhongwei) |

| Company Deputy Leader (副连职 fu lian zhi) | 1LT (中尉 zhongwei) | CPT (上尉shangwei) |

| Platoon Leader (排职 pai zhi) | 2LT (少尉 shaowei) | 1LT (中尉 zhongwei) |

Structural reforms pursued under Xi created additional problems for a primarily grade-based officer system.

However not only the military, but also the arms industry shall be modernized.In a synopsis “How developed is China´s Arms industry?”the CSIS gives the following analysis:

“The Chinese defense industry has undergone enormous changes in recent decades. Through much of the 1970s, China was primarily capable of producing weapons based on outdated Soviet technologies from the 1950s. Under Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, national defense was prioritized as one of the “four modernizations” which helped kickstart the growth of China’s domestic defense industrial base.2

Subsequent decades of economic development allowed the Chinese government to dramatically increase defense spending, leading to growing demand within China’s defense industry. China’s defense spending stood at just $26.1 billion (constant 2018 US$) in 1995, accounting for only 2.4 percent of the world total. By 2019, it had grown tenfold to $266.5 billion and accounted for 14.2 percent of global defense spending. In the same period, Russia’s defense spending doubled, and the US’ spending grew by 47 percent.

The Chinese defense industry has long relied heavily on anabsorptive model in which firms acquire foreign military and dual-use technology and incorporate this into the design and development of products. This approach has significantly reduced the amount of time and money China has had to invest in research and development (R&D), testing, and integration. This significantly sped up Chinese efforts to modernize its military and narrow technological gaps, especially in areas such as aviation, naval shipbuilding, and precision strike missile production.

China has used various means to acquire foreign military and dual-use technologies. In 2014, for example, several of China’s top arms companies signed a deal with Russian defense firm Russia Technologies (Rostec), including an agreement between AVIC and Rostec to collaborate on fixed-wing and helicopter manufacturing, engine production, aircraft materials, avionics, and other areas.In 2019, China spent an estimated $261.1 billion on its military – the second highest amount of any country besides the United States.

Chinese arms companies are not alone in reaping benefits from foreign cooperation. In 1998, India and Russia signed an agreement forming a bilateral joint venture known asBrahMos Aerospace to produce supersonic cruise missiles. In Japan, which is heavily reliant on US-made military equipment, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries is receiving help from Lockheed Martin to develop a new jet fighter.

However, in addition to legally acquiring foreign know-how, China has also illegally copied and stolen foreign military and dual-use technology. In the 1990s, China purchased Russian Su-27 fighter jets and S-300 missile systems and reverse-engineered them to assist with designing its J-11 fighter jets and HQ-9 surface-to-air missiles. In 2019, Russia’s Rostec accused China of illegally copying various equipment and technologies, including aircraft engines, planes, air defense systems, and missiles.

China has also engaged in sophisticated cyber espionage campaigns against the US. In 2007, 2009, and 2011, Chinese hackers gained access to some50 terabytes of US Department of Defense data containing the blueprints of American stealth fighters and other information. In 2016, Chinese national Su Binpleaded guilty to conspiring to steal data relating to Boeing’s C-17 strategic transport aircraft and Lockheed Martin’s F-35 and F-22stealth fighters. Two Chinese nationals, Zhu Hua and Zhang Shilong, were charged in 2018 with running a multi-year campaign to steal critical aviation, space, satellite, manufacturing, communications, computer processor, and other technologies.

These efforts highlight the difficulties China has faced in domestically producing certain military aviation equipment. Purchases of aircraft and engines accounted for 71 percent of the $6.3 billion in arms that China imported from 2015 to 2019. These purchases helped make China the world’s fifth largest arms importer behind Saudi Arabia, India, Egypt, and Australia.

Russia supplied 75.5 percent of China’s total arms imports during this period – including the bulk of the aircraft and engines. China has a long history of purchasing Russian military equipment dating back to the Korean War . Decades of tensions saw Russian exports to China cease, but following the rekindling of diplomatic relations between the two countries after the Cold War, China once again became a top purchaser of Russian arms.

Some of China’s most advanced systems are still reliant on Russian technology. For example, many of AVIC’s Chengdu J-20 stealth fighters employ Russian Saturn AL-31 engines. Versions of the Shenyang FC-31 jet fighter, produced by AVIC subsidiary Shenyang Aircraft Corporation, have likewise used Russian RD-93 engines. However, China appears to be making headway on replacing Russian engines. A domestically built WS-10C engine is reportedly being used in variants of the J-20, and new variants of the FC-31 are likely to be outfitted with Chinese WS-13E engines. Over the next decade, both planes are expected to feature more advanced Chinese-made engines, including the WS-15 and WS-19.

Prioritizing Innovation

China’s arms industry has historically favored lower-cost mass production over creating state-of-the-art weapons with high price tags. This has been crucial to affordably arming the PLA and has allowed Chinese firms to dominate segments of the global market with cost-sensitive customers. However, leaders are increasingly pushing to shore up domestic innovation capacities to lead in key technologies critical to national defense in the decades to come.

Chinese leaders acknowledge the weaknesses of the country’s defense industry and the need for China to push to the leading edge of innovation in military and dual-use technologies. China’s2019 defense white paper states that the country lags in critical defense technologies and concludes that “[g]reater efforts have to be invested in military modernization to meet national security demands. The PLA still lags far behind the world’s leading militaries.”

| Sector Breakdown of China’s 10 Major Arms Companies | |

|---|---|

| Sector | Company |

| Aerospace | |

| Aero Engine Corporation of China (AECC) | |

| Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC) | |

| China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC) | |

| China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) | |

| Electronics | China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC) |

| Land Systems | |

| China North Industries Group Corporation (NORINCO) | |

| China South Industries Group Corporation (CSGC) | |

| Nuclear | |

| China Academy of Engineering Physics (CAEP) | |

| China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) | |

| Shipbuilding | China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) |

| Source: China State Administration for Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense; SIPRI |

Even if one doubts the comparability of the figures, it is enormous that China’s defense spending increased tenfold from 2012 to 2019. At the same time, there was a slump in armaments exports, although the more detailed reasons are unfortunately not given and there is no regional analysis of the exports. It is interesting that so far, almost only low-end armaments from Chinese-Russia replicas have been exported, but at the same time the CCP promotes more the own national innovation and development of high tech weapons of Chinese origin- similar to India (while the Biden administration now urges Western allies not to buy Russian weapons ,e.g. India or Turkey and the S-400 anti-missile system). That the Russian complain that the Chinese are stealing technology from them is also funny. However, while China exports less low-end weapons, it remains to be seen if they will sell in the future more of their own hi tech innovations or hold them back because they fear that the US could get access and knowledge about their systems.

Untill now, there are only strange reports and photos avaiable about China´s alleged 3rd air craft carrier:

„China’s 3rd aircraft carrier expected to launch in 2021: reports By Liu Xuanzun Published: Jan 17, 2021 09:55 PM

What seems to be an aircraft carrier, covered by a red blanket, is seen in a report by China Central Television on Tuesday. Photo: Screenshot from China Central Television

What seems to be an aircraft carrier, covered by a red blanket, is seen in a report by China Central Television on Tuesday. Photo: Screenshot from China Central Television

China’s third aircraft carrier, expected to be very different from the previous two with much larger displacement and featuring electromagnetic catapults, could be launched in 2021 and enter naval service around 2025, media reports predicted based on recent photos of the ship’s construction site.“

https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202101/1213074.shtml

As the U.S.-China technological competition intensifies, the Chinese military has created new mechanisms to accelerate military innovation which are analyzed in The Diplomat in the article:“The PLA’s New Push for Military Technology Innovation„:

“Today’s Chinese Central Military Commission (CMC) S&T Commission does not have the name recognition of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in the United States. Nor does it have DARPA’s vision and research prowess. However, when the PLA reformers disbanded the General Armament Department (GAD), where the S&T Commission used to be housed, in 2016, the Commission was elevated to become one of the 15 first-level organs directly under the CMC. It began to play a much more prominent and direct role in guiding and advising PLA leadership on weapons development while serving as an intgernal dirver for collaboration between the PLA and Chinese defense industry to facilitatean internal driver military innovation. Most recently, it has begun actively exploring ways to construct a more open and inclusive culture that may be conducive to innovation.

On September 12, the CMC S&T Commission held itsfirst “Defense Technology Innovation Opewn House Day” (国防科技创新创意接待日) in Beijing. The event went mostly unnoticed in Western defense circles. Official Chinese media reported that 44 representatives from Chinese military and civilian universities, research institutes and technology companies participated in the event, during which key S&T Commission leaders engaged in face-to-face exchanges of ideas with the participants, and gave directives to relevant offices of the commission to take follow-up actions. Prior to the event day, the Commission verified and accepted a total of 755 ideas from the public through its online and mail-in submission platforms. The CMC now plans to host its Open House day on a monthly basis..

https://thediplomat.com/2020/10/the-plas-new-push-for-military-technology-innovation/

A study by the Mercator Institute for Chinese Studies (Mercis) claims that the PLA reforms are not that much orientated towards the USA, but more towards Russia´s military reform and Putin´s strategic doctrines:

“Learning from Russia: How China used Russian models and experiences to modernize the PLA

Main findings and conclusions

- This paper challenges the common assumption among military analysts that China’s military reforms are driven by strategic competition with the United States and inspired by changes in the US military as the sole template.

- China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been considerably influenced by Russian doctrine, force structuring and equipment from its inception and continues to draw heavily on the Russian experience.

- Since coming to power, Xi Jinping has used military reforms to reestablish firm control over the PLA in much the same way as Russian President Vladimir Putin wielded his role as Commander-in-Chief after the Russian military’s poor performances in Chechenya and Georgia.

- The establishment of the PLA Strategic Support Force (PLASSF) seems to have been inspired by the Russian model. China’s military officers and strategists continue to be schooled in Russian thinking on “new generation warfare” and have identified the Russian strategy as a key battle-winning factor.

- Joint training has become a major facet of Sino-Russian military cooperation and has been expanded from land, air and sea exercises to embrace sensitive fields like information and antimissile technology.

- Delving deeper into Russian military thinking and doctrines will be important to forecast the likely future trajectory of PLA reform.

1. Introduction: China’s military follows Russian models

China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was structured, trained and equipped by Stalin’s Soviet Army from its inception. The entire PLA military leadership cut their teeth in Russia and adopted Russian military doctrines, concepts and thinking in the early years of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Even when policy differences or the clashing egos of Mao Zedong and Nikita Khrushchev led to tensions, the PLA continued to rely on Russian military thinking. This has been especially true in the armaments and aviation industries.

In the 21st century, the 2001, Sino-Russian “Treaty of Good Neighborliness, Friendship and Cooperation,” signed by China’s then-president Jiang Zemin and Vladimir Putin, has provided the guiding framework for cooperation between Russia and China. It elevated the relationship to a strategic level, with both parties agreeing to consult in cases of “threat of aggression.”1

The Russian and Chinese leaders have reaffirmed this special relationship several times since, notably when China’s President Xi Jinping hailed the 2001 treaty as an example of a “new type of bilateral relation”2 on its fifteenth anniversary.

This paper challenges the common wisdom among military analysts that China’s military reforms are driven by strategic competition with the United States and inspired by changes in the US military. It is certainly true that US military prowess has triggered Chinese military thinking on upgrading PLA forces – for instance swift US military success in the invasions of Kuwait (1990-1991) and of Iraq in 2003 (whatever may be said about that mission’s later problems). More recently, the US display of technology and missilery in Syria, Afghanistan and Libya has stimulated rethinking. However, it is one-sided to view the US as the sole template. This paper argues that PLA reforms continue to draw heavily on the Russian experience as well.

The PLA has been considerably influenced by Russian doctrine, force structuring and equipment. There are compelling reasons for China to follow Russian models for military reform:

- Equipment homogeneity. China’s modern weaponry, including indigenously produced equipment, is basically the same as Russia’s.

- Geopolitics. China and Russia are traditionally land-centric countries that share a long border and similar geography. There is a convergence of thinking on the roles envisaged for their militaries. Both militaries also originate in similar political systems and socio-political habits.

- Basic military strategy and doctrine. The fundamental military strategy adopted by both is ‘strategic defense’, or as the PLA’s stated military strategy calls it, ‘active defense’. Turning to perceived internal threats, both nations identify challenges from the “three evil forces” of separatism, terrorism, and religious extremism. PLA thinkers have studied Russia’s counter-insurgency strategy in Afghanistan and the Chechnya wars in great detail.3

- International military security. According to PLA sources, China and Russia have cooperated in safeguarding the international nuclear non-proliferation regime; in promoting denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula; countering terrorism; maintaining cyber security; opposing the militarization of space; and encouraged the cessation of Cold War mindsets in many countries.

2. Russian and Chinese “revolutions in military affairs”

The term Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) denotes major, interconnected changes in strategies, doctrines, equipment, organization and structures that aim to fundamentally alter a nation’s approach to warfare.4 In general, militaries are changeaverse and require a “top down” directive to undertake revolutionary or disruptive changes. For instance, it took the US Senate’s Goldwater-Nichols Act in 1986 to push through a deep transformation of the US army. China’s Goldwater-Nichols moment came in 2012 when Xi announced the creation of five Joint Theatre Commands and other groundbreaking directives.

In many ways, recent Russian and Chinese RMAs appeared to share a similar fundamental aim, namely to shift from “protracted large scale conventional military conflict in the 1980s into a more compact, high technology military to engage in swift and intense securing of operational aims in the twenty-first century.”(…)

4. China’s military relations with Russia today

4.1 Joint training

As a result of strategic consultations at the highest levels of government, joint training became a major facet of military cooperation within the Sino-Russian relationship. Joint military exercises began in 2005, and were expanded from land, air and sea exercises to embrace new and sensitive fields e.g. information and antimissile technology. Likewise, the scope of these exercises has grown to cover the entire spectrum from the tactical to the strategic levels.38 They advance mutual understanding, and play a significant role in the enhancement of combat capability and strategic deterrence.39 Such exercises have facilitated:

- the showcasing of Russian weapons to PRC military commanders, thereby promoting weapons sales to China, e.g., sales of the S-400 Triumf Air Defense System and IL-78 tankers.40

- greater interoperability between the two militaries.

- important training opportunities, as the PLA’s lack of battle experience (it has not fought a war since 1979) is offset by live and confrontational exercises to learn new tactics, techniques and procedures.41 Naval exercises have included conduct of joint operations at sea to train against non-traditional threats like terrorism, gunrunning, piracy etc.

- the training of a cadre of linguists within both militaries who assist as translators to facilitate interoperability

- joint operations to deter threats to member states of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).42

4.2 Military technology cooperation

In the 1950s, China’s defense industry benefited greatly from the availability of Soviet technology and armaments, which were later reverse-engineered and indigenized. The Sino-Soviet split interrupted those efforts, and large-scale cooperation on military technology only resumed around 1993. Russian arms sales to China, including the transfer of major weapons systems and defense technology as well as licensing agreements, have yielded benefits for both sides.43

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIP-RI), China has procured defense equipment worth 35.3 billion USD since 1990, which was 77.8 percent of its total imports for the same period.44 In recent years, China has acquired Russian engines for its newest fighters and bombers, which are more reliable and perform better than its own versions. Russian engines are used on all three of China’s indigenous fourth-generation fighter lines. China also seems interested in outfitting its prototype fifth-generation J-31 fighters with next-generation Russian engines45.

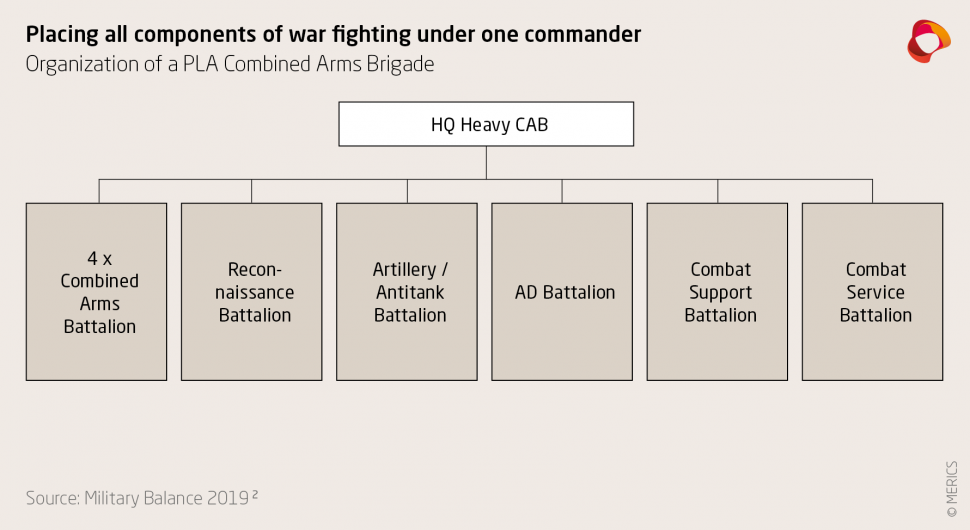

4.3 Mechanisation and firepower

The PLA has also undertaken a massive upgrade to mechanised units. As all PLA mechanised formations are equipped with Russian derivatives, they continue to imbue the same philosophy. The PLA’s modern Type 96 (similar to T-72) or the older T-59/ T-62/T-63, or even the ZBD-03/ZBD 04/WZ-551/ WZ-553 series of ICVs, are all of Russian design and focus on better and accurate firepower rather than manoeuvre. The PLA’s ‘Heavy’, ‘Medium’ or ‘Light’ CABs appear to have adopted the doctrine of mechanisation, including reorganisation and equipping norms akin to Russian Mechanised forces.

The phenomenal increase in the firepower component, especially Long Range Vectors, Multiple Launch Rocket Systems, Multiple Barrel Rocket Launchers and Drones/UAV, in the Combined Armies and Motorised Brigades seems to suggest that the PLA may be following the Russian model in viewing the deployment of artillery as a “finishing arm” Today’s CABs are supported by an integrated artillery battalion, an artillery battery in each battalion of the CAB, in addition to the artillery brigade at the Corps level.

These two major shifts in operational level concepts will directly drive the PLA’s approach to equipment, manpower recruitment needs and training in the future. Military thinkers and operational commanders need to focus on the development of these concepts to extrapolate and predict the PLA’s future trajectory as it aims to become a modernised military by 2035. Its relationship with Russia is key for this analysis, as has been aptly summarized by Russian journalist Maxim Trudolyubov: “On the political front, Russia feels like a China understudy. On the Military front, Russia, is a country that has gone through transformative reforms and modernization and is definitely the leader and China is more the understudy. Russia’s military reforms preceded China’s reforms by quite some time.”46

Delving deeper into Russian military thinking and doctrines will be important to forecast the likely future trajectory of the new look PLA.

SourcesDownload (pdf – 1.85 MB)Foreign Relations Author(s)

However, German sinologist Prof. Van Ess questions the assumptions and conclusions of the Mercis study:

“Mercator is behind Merics. And they have a very clear agenda.Mercator is one of the spearheads of the so-called „civil society“ (a word that, beginning in the 90s and then with tremendous acceleration since 2000, has had a fairytale career comparable to the stock indices). From my point of view, it is a matter of dividing the world into states in which NGOs are allowed to teach governments to a certain extent what politics should look like, and those that do not allow it. This leads to an emphasis on transatlantic relations. I think these analyzes are of little help. Of course, since Gorbachev’s visit in May / June 1989, Russia and China have strategically allied themselves. And of course, the democratic centralism of China is a Russian invention that also extends to the military sphere. This is nothing new. But of course there is great admiration for the American military, whose successes one would like to copy.”

Of course, this allegedly one-sided orientation is questionable. Usually the Chinese look at several militaries and try to learn what they think can be useful, and of course the CCP also sees the US military as its most likely challenger. They also try to emancipate themselves from Russia in terms of armaments. And the question is whether they can in a war for Taiwan and the South China Sea need Russia´s experience from Afghanistan, Syria and Libya or were more impressed by the Iraq wars and the RMA. Besides, Russia has no Silicon Valley, but only this mediocre Skolkovo and russky hi tech parks.

And the old question remains: Does China want to project military power globally?

Many analysts believe China wants to be the dominant military power in the Asia-Pacific, capable of deterring and, if needed, defeating the United States in a future conflict. But it’s unclear whether China’s ultimate ambition is to project power throughout the world, much like the United States does today.

The Chinese government said in its 2019 white paper that it will “never threaten any other country or seek any sphere of influence.” It maintains a no-first-use nuclear policy, has no military alliances, and claims to oppose interference in other countries’ affairs.

Joel Wuthnow, a China expert at the U.S. National Defense University, told CFR that, at least in the near term, the PLA will be kept busy close to home. “China is still a long way from becoming a global force like the U.S. military because their attention is confined to the region,” he says.

Yet, as Beijing’s economic interests expand through Central Asia and Europe—part of its Belt and Road Initiative—the military could increasingly be called to operate abroad. Some U.S. officials warn that the colossal development project could eventually be used for military purposes. However, Beijing claims this is untrue, with most projects currently protected by Chinese security companies.

China opened its first overseas base in Djibouti in 2017, despite swearing off bases in one of its first white papers nearly two decades earlier. There were reports in 2019, which Chinese officials denied, that China was constructing another base in Cambodia. China has conducted an increasing number of joint military exercises, including with Pakistan, Russia, and members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. PLA service members also participate in UN peacekeeping missions, with more than 2,500 active peacekeepers as of 2019.

In his article “How China Sees the International Order: A Lesson from the Chinese Classics “ at War on The Rocks, David K. Schneider claims that Chinese state craft and perception of the international anarchic order is more originating form classical thinking of the Spring, Autumn and Warring States period of Chinese history and the classic book Zuozhuan than only in Sun Tzu or the strategemas.

“Many Western analysts and international relations scholars take the intellectual and historical foundations of statecraft for granted. They invoke the ”Thucydides trap” when pondering whether the world will be able to accommodate China’s rise and cite Machiavelli when thinking about Beijing’s practice of realpolitik. While these perspectives are important and useful, they tend to interpret the problem of Chinese global power in analytical terms derived only from the Western intellectual and historical experience. Chinese foreign policy thinkers know the Western canon, of course. But China has its own rich intellectual tradition that informs its statecraft just as deeply as the Western tradition informs that of North America and Europe.

The Chinese strategic canon contains sophisticated debates that cover most of the categories that comprise modern international relations. There are, for example, concepts analogous to Western ideas of both liberal internationalism and of realpolitik, or realism. But it is also important to understand at what points Western and Chinese concepts diverge. I argue that while Chinese and Western views are quite similar on the subject of realism, they differ on the subjects of international cooperation and the rules-based order. This mismatch is important because the strategic goal of the United States over the past three decades has been to somehow induce Beijing to abandon its own concept of a hierarchical international order and to submit to a rules-based and liberal one. A look into the Chinese strategic canon, specifically the story of “Zhu Zhiwu Persuades Qin,” shows why this goal is unattainable.

Introduction to the ‘Zuozhuan’

The origins of the Chinese intellectual tradition of statecraft lie in the chaotic time after 771 B.C. when the formerly unifiedZhou kingdom began to disintegrate. Consisting of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, this time holds roughly the same position in Chinese political thought as the classical age holds in the West. These centuries saw feudal city-states vying by means of diplomacy and war to survive or dominate an increasingly anarchic world system. This experience brought forth one of the most important books of the Chinese canon, the Zuozhuan, a veritable treasure trove of statecraft, war and diplomacy

(…) Yet, American policy since the normalization of relations in 1979 has prioritized the integration of China into the American-sponsored liberal international order, understood as involving democracy, global capitalism, and freedom of international navigation. The administrations of George Bush and Barack Obama both sought to convince China that it was in its own self-interest to become not only a “responsible stakeholder” but also a key sponsor of the American order. This line of thinking was most recently reaffirmed by the anonymous author of ”The Longer Telegram ” which asserts that the “foremost goal of US strategy should be to cause China’s ruling elites to conclude that it is in China’s best interests to continue operating within the US-led liberal international order rather than building a rival order.” This, as we see here, is at odds with the vision of international order articulated in the Zuozhuan and in centuries of historical experience thereafter. It is not simply that China sees the present liberal order as unequal and dominated by the United States. Beijing is asserting an entirely different geopolitical order as the legitimate one rooted in its own intellectual tradition and in its experience of Asian history.

Reading the Chinese strategic canon provides a perspective on Chinese geopolitical thought and practice impossible to achieve with methods derived from Western international relations theory or from the history of Western strategic thought. Analysis of the vignettes contained in books such as the Zuozhuan can help shed light on why Beijing has resisted Western calls to be a responsible stakeholder and can suggest ways to think through differences between Chinese and Western approaches to statecraft and diplomacy. These vignettes also highlight the need for a more comprehensive and global strategic canon. When we speak of Machiavellian realism, we will increasingly need to think of it in comparison to the realism of the Chinese tradition demonstrated by figures like Zhu Zhiwu. And when we consider the requirements of a rules-based international system, we will need to make the same comparisons with Chinese views of global order found in the philosophy and actions of Duke Wen of Jin and his successors.”

John Sullivan in his article “Trapped by Thucydides? Updating the Strategic Canon for a Sinocentric Era” is already critizising the Western categories of thinking as Harvard professor Graham Allison´s term Thucydides trap”which dominates the mainstream discussion in the USA. The better approach to Chinese strategic and military thinking was reading the Zuozhuan:

“The lessons from the Zuozhuan imply that great-power permanence rests on two pillars: internal domestic stability and skillfully managed alliances. Despite China’s impressive economic and military growth, its domestic support remains brittle and it struggles to formlasting and mutually beneficial partnerships. Although the United States has traditionally been relatively strong in these two areas, since at least the turn of this century, the bases of these pillars have eroded quickly. If America hopes to avoid a zero-sum conflict with China over the fate of the international system, it would be prudent to begin repairing and strengthening these supports.

Conclusion

This brief survey only scratches the surface of potential areas of inquiry illuminated through study of the Zuozhuan. Another subject ripe for additional research is military theory. In the West, the study of ancient Chinese military thinking rarely ventures beyond Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. This is unfortunate, because thecontext provided by Zuozhuan can help Westerners better understand many ofSun Tzu´s more vahue pronouncements. The few historical references found in The Art of War, such as the rivalry between the states of Wu and Yue or the courage of figures like Cao Gui and Zhuan Zhu, are explained within the Zuozhuan narratives. Moreover, the text allows us to expand our scope of analysis beyond one individual viewpoint. The Zuozhuan references other military texts extant at that time, such as the Book of Military Maxims (軍志), reminding us that a rich body of strategic thinking existed in China outside the confines of Master Sun’s work.

Alas, the Zuozhuan demands much of any potential reader, particularly one not well versed in its specific milieu. It will resist easy inclusion into any university or war college syllabus. Similar to Thucydides’ work,fierce millennia old debates exist over its authorship, date of composition, historical accuracy, as well as every aspect of its purported meaning. It can also be a frustrating book. Those attempting to make sense of its temporally fractured narratives or cast of several thousand individuals and locations (some with at least a half-dozen variations on their name) will long for the simplicity of trying to discover if Thucydides is referencing Naxos in Sicily or the one in the Aegean. But those who persist will be rewarded with a complex and rich historical narrative of no less impressive depth and breadth than the most venerated works of their Hellenic cousins.

Thucydides’ work has earned its exalted status in the study of strategic thought. However, analysis of other cultures’ struggles to achieve peace and security in roughly comparable eras of great-power competition might stimulate new thinking on old problems. As Confucius once noted, “If you can revive the ancient and use it to understand the modern, then you’re worthy to be a teacher.” In that effort, we should resist limiting the scope of our inquiries to only Western historical examples. Through study and synthesis of the failures and shortcomings of all of our distant forefathers, we might gain wisdom to forge a new and better path forward.“

This debate had been held recently between John Mearsheimer and Kishore Mabubhani, as well as by Parag Khanna in his book The Future is Asian. Mabhubani and Khanna think that China in the future won´t copy the USA and classic superpower features, but orient more to a traditional tribute system comparable to earlier dynasties in a new form and according to Chinese classical writings. Mearsheimer as masterbrain of the new offensive realism thinks that China will behave like every other superpower before and that not classical writings, Sun Tzu or esoteric Far East philosophical thinking , Go playing or alleged Chinese wisdom would shape its future behaviour, but the brute force of realism. Kishore Mabubhani,Parag Khanna , John Sullivan,David K. Schneider, the greatest China admirer and alleged real politican and historian of all times Henry Kissinger (and his friend Helmut Schmidt and Lee Kuan Yew) and other culturalists claim that the Chinese history and its classical writings are the roots of understanding of the future form of Chinese expansionism and that China doesn´t want to be a neocolonial or neoimperialist power as the West, the Europeans or the USA was and is, that China was adopting another pattern for a peaceful rise as warrior states like the Western powers and who wouldn´t understand that was historical ignorant, cultural uninformed and a primitive cowboy- Gung ho-culture barbarian with no sense and deeper knowledge about the oldest civilization.

John Mearsheimer and other offensive realists and US politicans however think that this is not important, that you cannot compare ancient with modern China and superpowers and that there will be no peaceful rise, that all this talk about it and culturalist approaches are just propaganda and camouflage by the CCP to blind naïve Westerners and to appease them as China did before, play with their fear to be portrayed as an cultural illiterate, but that China will behave like the USA if is getting strong enough, at latest in 2049., at the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People´s Republic of China.On the one hand one has to be a little cautious when people think of a certain era of Chinese history as the actual classical China and the eternal source of today’s Chinese state craft, on the other hand, different periods are often cited as style-forming as this is also a little bit speculative, and thirdly, there is often no empirical reference to the curriculum of today’s Chinese state leaders and their factual politics. And Chinese thinking, if there is 1, was also influenced by other periods and other authors and even Western ways of thinking and might be more syncretical and might change again due to new historical events. And Zuozhuan as Mearsheiemr´s offensive realism as realism and neorelaism have also the minimal common denominator of an anarchic state order.

However, whatever the source of Chinese thinking might be, the CCP´s mouthpiece the Global Times gives the USA a lecture what it still has to learn to come in terms with China:

“Six points China has to let US understand: Global Times editorial

By Global Times Published: Mar 18, 2021

(…)

China believes that communication is always necessary because the US has an overall misjudgment about China. Whether through diplomatic contacts, through exchanges of opinion, or through the constant verification of words with real actions, China wants the US to gradually understand some of its basic positions and the sources of its confidence in defending them.

First, China has no geopolitical ambitions in the Asia-Pacific region. China’s development is driven by the desire of more than 1 billion people to pursue a better livelihood. Further satisfying this desire is the fundamental focus of China’s political governance. China does not believe that it has the ability, or that it is necessary, to pursue development by imperialist expansion. It has been proven by history that cooperation based on mutual benefit with other countries is more reliable and effective.

Second, China has explored a set of domestic governance methods that suit its national conditions. There are some ideological differences between China and the West, but China has no hostility toward the West. China has, since ancient times, always been an exponent of keeping harmony in diversity. The US initiated the strategic containment of China, which has deteriorated China‘ s security environment, forced China to speed up the development of its military power and carry out tit-for-tat ideological struggle. However, China has been maintaining its defensive strategy toward the West.

Third, China will never accept US interference in its internal affairs. How the US consumes the so-called human rights domestically is its own business. China will never give foreign forces a window to exercise long-arm jurisdiction on its internal affairs. What China can do is to help the US understand China’s political logic and the moral basis for all its governance measures. Such a dialogue does not mean that China is likely to yield to any US pressure.

Fourth, it is true that China has territorial disputes with some of its neighbors, but China’s consistent position on these disputes is to resolve them peacefully. China has always advocated that territorial disputes should not become the dominant aspect of bilateral relations and should not interfere with cooperation between China and other countries. China is firm in its position of managing territorial disputes.

Fifth, it is China’s sacred right to develop. China has never contemplated as a geopolitical goal the possibility of overtaking the US in economic growth in a few years, nor has China ever considered replacing US hegemony with „Chinese hegemony.“ It is Beijing’s sincere hope that the 21st century will be a century of win-win results for China, the US and other countries. China’s development will not be a zero-sum victory only for China, but should become shared benefits worldwide.

Sixth, the Chinese are confident that they are capable of defending their own national security, and no matter how hard the US tries, it cannot contain China. If the US is willing to coexist and cooperate with China in peace, China welcomes that and will work hard to make that relationship work. If the US is determined to engage in confrontation, China will fight to the end.