Putin bindet Belarus weiter an, China Zentralasien

Während manche auf einen Waffenstillstand hoffen auf eine Deskalation, gibt Putin neue Drohungen aus:

„Putin kündigt Stationierung von Atomwaffen in Belarus an

- Aktualisiert am 25.03.2023-20:56

Der belarussische Machthaber Lukaschenko habe schon lange darum gebeten, atomare Waffen auf seinem Staatsgebiet zu stationieren, sagt der russische Präsident im Fernsehen. Der Bau notwendiger Vorrichtungen habe bereits begonnen.

Russlands Präsident Wladimir Putin hat die Stationierung taktischer Atomwaffen in der ehemaligen Sowjetrepublik Belarus angekündigt. Darauf hätten sich die Führungen in Moskau und Minsk geeinigt, sagte Putin am Samstagabend dem Staatsfernsehen. Russland verstoße damit nicht gegen den internationalen Atomwaffensperrvertrag. Der Kremlchef verwies darauf, dass auch die USA bei Verbündeten in Europa Atomwaffen stationiert haben. „Wir machen nur das, was sie schon seit Jahrzehnten machen.“ Belarus ist sowohl Nachbarland Russlands als auch der Ukraine.

Die USA haben auch in Deutschland Atomwaffen stationiert. Putin hatte in der Vergangenheit deren Abzug gefordert, weil Moskau sich dadurch bedroht sieht. Nun betonte der Kremlchef, dass Russland – wie die USA – seine Atomwaffen keinem anderen Land überlasse. Vielmehr würden sie dort vorgehalten, und es gebe eine Ausbildung an den Waffen. Putin kündigte an, dass die entsprechenden Schulungen in Belarus am 3. April beginnen sollen. Die Schächte für die mit atomaren Sprengköpfen bestückbaren Iskander-Raketen sollen am 1. Juli fertig sein. Aus Minsk gab es dazu zunächst keine Angaben.

Putin empört über mögliche Lieferung von Uranmunition

Belarus und dessen Machthaber Alexander Lukaschenko gehören zu Moskaus engsten Verbündeten. Lukaschenko habe immer wieder um die Stationierung taktischer Atomraketen gebeten, sagte Putin. Der Dauer-Machthaber in Minsk – oft als „letzter Diktator Europas“ bezeichnet – hatte auch bedauert, dass Belarus sich nach dem Zusammenbruch der Sowjetunion vor mehr als 30 Jahren von seinen Nuklearwaffen trennte. Auch die Ukraine hatte damals ihre Atomwaffen aufgegeben.

Russland habe Belarus schon beim Umbau von Flugzeugen geholfen, von denen nun zehn so ausgerüstet seien, dass sie ebenfalls taktische Nuklearwaffen abschießen könnten, sagte Putin. Taktische Atomwaffen haben eine geringere Reichweite als Interkontinentalraketen, aber auch noch mehrere Hundert Kilometer. Die Sprengwirkung liegt zwischen 1 und 50 Kilotonnen TNT. Russland stationiert aber keine strategischen Atomwaffen in Belarus, die etwa die USA erreichen könnten.

Mit der Stationierung reagiert Russland auf die zunehmenden Spannungen mit der NATO im Zuge von Putins Krieg gegen die Ukraine. Russland war vor mehr als einem Jahr in die Ukraine einmarschiert. Konkret empörte sich Moskau zuletzt über die mögliche Lieferung von Uranmunition aus Großbritannien an die Ukraine. Die Geschosse mit abgereichertem Uran haben eine besondere Schlagkraft, um etwa Panzer zu zerstören.

Putin warnte im Staatsfernsehen vor dem Einsatz solcher Munition. Uranmunition gehöre „zu den schädlichsten und gefährlichsten für den Menschen“, da der Uran-Kern radioaktiven Staub verursache und die Böden verseuche. „Wir haben ohne Übertreibung Hunderttausende solcher Geschosse“, sagte er. Bisher seien sie aber nicht eingesetzt worden.

NATO hat Atombomben in mehreren europäischen Ländern stationiert

Die britische Armee verwendet seit Jahrzehnten abgereichertes Uran in panzerbrechenden Geschossen. Das Verteidigungsministerium in London warf Putin Falschinformation vor, nachdem er von einer „nuklearen Komponente“ gesprochen hatte. Putin wisse, dass dies nichts mit nuklearen Waffen oder Fähigkeiten zu tun habe.

Die USA haben im Zuge der atomaren Abschreckung der NATO Atombomben in mehreren europäischen Ländern stationiert. Offizielle Angaben gibt es dazu zwar nicht, es sollen aber weiterhin in den Niederlanden, Belgien, Italien und Deutschland Atomwaffen lagern – außerdem im asiatischen Teil der Türkei. Mit Großbritannien und Frankreich besitzen weitere NATO-Staaten eigene Atomwaffen.

Auf dem Bundeswehr-Fliegerhorst Büchel in der rheinland-pfälzischen Eifel sollen noch bis zu 20 US-Atombomben stationiert sein, die im Ernstfall mit Tornado-Kampfjets der Bundeswehr eingesetzt werden sollen. Die in Büchel stationierten Tornados sollen ab 2027 durch moderne Kampfjets aus US-Produktion vom Typ F35 ersetzt werden.

In dem Interview sagte Putin auch, dass Russland angesichts der westlichen Panzerlieferungen für die Ukraine die eigene Panzerproduktion erhöhen werde. „Die Gesamtzahl der Panzer der russischen Armee wird die der ukrainischen um das Dreifache übertreffen, sogar um mehr als das Dreifache.“ Während die Ukraine aus dem Westen 420 bis 440 Panzer bekomme, werde Russland 1600 neue Panzer bauen oder vorhandene Panzer modernisieren.

Putin sagte zudem, Russland könne das Dreifache der Munitionsmenge produzieren, die der Westen der Ukraine liefern wolle. Die nationale Rüstungsindustrie entwickle sich in hohem Tempo. Allerdings wolle er die eigene Wirtschaft nicht übermäßig militarisieren, behauptete der Kremlchef. Tatsächlich wurde in Moskau bereits eine Regierungskommission gegründet, die kontrollieren soll, dass die Wirtschaft den Anforderungen des Militärs gerecht wird. Während die russische Wirtschaft schwer unter den westlichen Sanktionen leidet, arbeitet die Rüstungsindustrie auf Hochbetrieb.

Soll man nun taktische Atomwaffen in Polen oder im Baltikum stationieren? Inwieweit ist denn die NATO-Russland-Grundakte noch wichtig?

Die Briten sollen jedenfalls sofort die Lieferung von Uranmunition einstellen .Ebenso die Ukraine ihre Forderungen nach Streubomben und anderen völkerrechtswidrigen Waffen-wobei das Stoltenberg ja auch abgelehnt hatte ,um noch einen moralischen und humanitärpropagandistischen Unterschied zwischen West und Putin aufrecht zu erhalten.

Würde die Stationierung taktischer Atomwaffen in Belarus etwas an der nuklearen Abschreckungsbalance ändern, wie auch in Kaliningrad die Iskander.Ist das mit den SS 20 vergleichbar

Die von Focus befragten Experten von Henfried Münkler zu Thomas Jäger sehen das im Wesentlichen gelassen, es sei nur eine Drohgebärde, um den Westen zu verunsichern und Angst zu erzeugen, eher ein Zeichen der politischen und militärischen Schwäche, wie es auch an der nuklearen Balance nichts entscheidendes verändern würde.

„Mit Atomwaffen in Belarus verfolgt Putin drei Ziele

(…)

Putin wolle Weißrussland noch enger an Russland binden

Mit der Stationierung der Atomwaffen in Berlarus verfolge Putin vor allem das Ziel, Weißrussland noch enger an Russland zu binden und noch mehr Kontrolle über das Land zu gewinnen, erklärt Thomas Jäger, Professor und Inhaber des Lehrstuhls für Internationale Politik und Außenpolitik. . Doch „Weißrussland hat nur noch eine eingeschränkte Souveränität, Putin vereinnahmt das Land auf kaltem Wege“, so der Außenpolitik-Experte.

Jäger sieht aber noch zwei weitere wichtige Ziele Putins: Das zweite sei, die USA abzuschrecken, ihrerseits Atomwaffen dichter an Europa zu stationieren. Jäger sagt aber auch: In dieser Hinsicht würde sich nicht viel ändern, „denn in Kaliningrad können schon jetzt Atomwaffen stationiert werden, deshalb werden nicht einmal die Vorwarnzeiten verkürzt“, erklärt er weiter. Das Ziel diene eher der Propaganda.

Das dritte Ziel sei, so Jäger, Angst in den europäischen Gesellschaften zu schüren. Zum einen allgemein vor einer Eskalation des Krieges, zum anderen vor der Verwundbarkeit der europäischen Staaten durch die kurzen Vorwarnzeiten.

„Zeichen politischer und militärischer Schwäche“

Für den Außenpolitik-Experten sei es nicht verwunderlich, wenn im Rahmen der jetzt erweiterten Informationsoperation dieses Thema in den nächsten Wochen intensiver durch die europäischen Desinformationsverbündeten Russlands in die Öffentlichkeit getragen wird. Doch Jäger glaubt nicht, dass Putin dies gelingen wird: „Da Putin und sein Umfeld nun schon seit einem Jahr mit dieser Angst spielen, nimmt der angestrebte Schrecken ab“.

Nach Einschätzung des Außenpolitik-Experten ist Putins Vorgehen vielmehr ein Zeichen militärischer und politischer Schwäche: militärisch, weil Russland den Krieg nur gewinnen kann, wenn der Westen die Unterstützung der Ukraine einstellt. Denn aus eigener Kraft könne Russland die Ukraine nicht besiegen. Und politisch, so Jäger, sei es ein Zeichen der Schwäche, weil Putin keine politisch-strategischen Optionen mehr habe. „Er hat den Krieg auch politisch verloren“, so Jäger.

„Komplementäre Druckmittel zu dem Lieferstopp von Erdgas und Erdöl“

Für Herfried Münkler, emeritierter Professor für Politikwissenschaft an der Berliner Humboldt-Universität, hat Putin mit der Ankündigung „eine weitere Drehung an seiner Schraube einer Politik der Verängstigung vorgenommen“. Putin versuche damit, den Westen und insbesondere Europa von Waffenlieferungen an die Ukraine abzuhalten, sagte Münkler FOCUS online.

Dies sei das „komplementäre Druckmittel zu dem Lieferstopp von Erdgas und Erdöl“, so der Experte. Nachdem der Lieferstopp nicht den gewünschten Erfolg gebracht hat, setze Putin nun wieder auf die atomare Drohung, die er seit den ersten Rückschlägen im Krieg gegen die Ukraine immer wieder ins Spiel gebracht hat, erklärt Münkler. Was dieses Mal anders ist: Er droht nicht mit dem Einsatz taktischer Atomwaffen, sondern verlegt sie nach Weißrussland. Damit aber breche er eine weitere Vereinbarung, nämlich das mehrfach bekräftigte Budapester Abkommen, wonach die Ukraine und Weißrussland sowie andere ehemalige Sowjetrepubliken frei von Atomwaffen bleiben sollen, so Münkler.

Putin sei jederzeit zu riskanten Eskalationsschritten bereit

Putin rechtfertige sich zwar damit, dass auch der Westen seine Verpflichtungen nicht eingehalten habe, doch das sei falsch, so Münkler. Denn auf dem Gebiet der ehemaligen Warschauer-Pakt-Staaten seien keine US-Atomraketen stationiert. Für den Experten ist klar, dass es Putin darum geht, seiner Forderung vom Dezember 2021, die US-Atomwaffen aus Europa abzuziehen, neuen Nachdruck zu verleihen. Denn das hieße, den US-Atomschirm über Europa einzurollen und Europa politisch erst recht der russischen Erpressung auszuliefern.

Dennoch erklärt der Experte, dass Putins Pläne nichts an der nuklearen Einsatzbereitschaft Russlands geändert hätten. „Es zeigt aber, dass Putin jederzeit zu riskanten Eskalationsschritten bereit ist, wenn er seine politischen Ziele nicht erreicht“, so Münkler.

Lukaschenko sprach im November 2021 bereits von Atomwaffenstationierung

Bereits im Januar 2022 prognostizierte die US-amerikanische Denkfabrik „ The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) “ eine russische Stationierung von taktischen oder strategischen Atomwaffen in Weißrussland. Zuvor hatte Lukaschenko am 30. November 2021 angeboten, russische Atomwaffen in Weißrussland zu stationieren.

Dass Putin nun, mehr als ein Jahr später, diesen Schritt ankündigt, kommt daher für viele Experten und Expertinnen nicht überraschend. So auch für Nico Lange , Senior Fellow der Initiative Zeitenwende bei der Münchner Sicherheitskonferenz: „Unmittelbar nach dem russischen Angriff auf die Ukraine hat Weißrussland in einem Referendum am 27. Februar 2022 die Verfassung geändert, um die Stationierung russischer Atomwaffen zu ermöglichen“, schreibt der Experte auf Twitter. Das Referendum wird jedoch von den westlichen Staaten nicht anerkannt – Grund dafür ist die brutale Unterdrückung der Opposition in Weißrussland.

Gefährliche Eskalation oder leere Drohung?

Die Kampagne zur Abschaffung von Atomwaffen (ICAN) warnt dagegen vor einer „extrem gefährlichen Eskalation“, nachdem der russische Präsident Wladimir Putin die Stationierung taktischer Atomwaffen in Weißrussland angekündigt hat. Die mit dem Nobelpreis ausgezeichnete Organisation in Genf ist der Ansicht, dass diese Pläne zu einer Katastrophe führen könnten und die Wahrscheinlichkeit eines Einsatzes solcher Waffen erhöhe. Die Stationierung von Atomwaffen in Weißrussland würde die Sicherheitslage in Europa destabilisieren und den Druck auf andere Länder erhöhen, ebenfalls Atomwaffen zu erwerben.

Nico Lange hingegen schreibt auf Twitter, dass Putins Ankündigung nichts an der Einschätzung der nuklearen Bedrohung durch Russland ändere. Lange schätzt die Gefahr eines russischen Atomwaffeneinsatzes als sehr gering ein. Der Experte schreibt weiter: „Es ist ein Fehler, bei jeder Erwähnung von Atomwaffen durch Putin aufgeregt von ‚Eskalation‘ und ‚Gefahr‘ zu sprechen. Das will er ja gerade.“ Gelassen zu bleiben sei ihm zufolge die bessere Reaktion.

Wie auch so manche Militärs dies auch für einen weiteren Versuch halten, ängstliche Gemüter im Westen, vor allem in Deutschland, mit Angst vor bevorstehenden Atomeinsatz zu beeindrucken. So meinte etwa auch ein ehemaliger hochrangiger deutscher NATO- General , dass dabei ein Einsatz taktischer Atomwaffen militärisch wenig sinnvoll sei, weil er Putin keineswegs den Sieg in der Ukraine bringen würde, ihn aber weltpolitisch noch weiter isolieren und vermutlich auch sein Verhältnis zu China nachhaltig belasten würde. Die Stationierung bringt auch keine militärpolitischen Vorteile, denn er hat bereits Atomwaffen im Oblast Kaliningrad und von den Reichweiten her braucht er Belarus in keiner Weise. Was ihm dagegen Vorteile verschaffen könnte, ist die mit der Verlagerung von Atomwaffen automatisch verbundene Stationierung von Truppenteilen des FSB, die man natürlich auch nutzen kann, sollte in Belarus die Innenpolitik ins Wanken geraten.

Dass es sich eher um ein Zeichen militärischer und politischer Schwäche handelt zeigt sich auch daran, dass bei allen Nachschublieferungeproblemen des Westens Putin ja auch ein Problem zu haben scheint ,wenn er die Verdreifachung der Panzerproduktion und Umstellung auf totale Kriegswirtdchaft grossmäulig ankündigt. Medjedew schafft ja nicht einmal die einfache Produktion, sieht überall Sabotage und droht nun den Rüstungsarbeiter und Rüstungsmanagern Strafen wie unter Stalin an. Das klingt eher recht verzweifelt.

„Zu wenig Nachschub: Medwedew droht Panzer-Industrie mit Stalin-Strafe

Erstellt: 26.03.2023, 17:01 Uhr

Sorge vor der Großoffensive der Ukraine: In Russland fehlen Panzer. Ex-Präsident Medwedew hat der Industrie bereits Strafe angedroht – in Stalin-Manier.

Moskau – Die hohen Verluste zeigen Wirkung: In Russland wird die Panik vor einer drohenden Niederlage im Ukraine-Krieg offenbar immer größer. So befürchtet der Kreml einer bevorstehenden Großoffensive der ukrainischen Truppen möglicherweise nicht mehr gewachsen zu sein. Das Umfeld von Präsident Wladimir Putin sei „tief besorgt“ über die Auswirkungen neuer Angriffe, schreibt die US-Denkfabrik „Institute for the Study of War“ (ISW) in einer neu veröffentlichten Analyse. Ein großes Problem scheint dabei vor allem die schleppende Produktion der heimischen Waffenindustrie zu sein.

Ukraine-Krieg: Dmitri Medwedew warnt Russlands Generalstab vor Offensive

Laut dem ISW-Bericht soll Ex-Präsident Dmitri Medwedew im russischen Generalstab bereits auf die brisante Lage aufmerksam gemacht haben. Es sei bekannt, dass Kiew eine Offensive im Ukraine-Krieg vorbereite und dass Russland sich darauf vorbereiten müsse, wird er aus der Sitzung zitiert. Jedoch kämen die Angriffe wahrscheinlich zu einem Zeitpunkt, so die Warnung, bevor Russland seine Militärkapazitäten erhöht habe.

In den vergangenen Wochen und Monaten hatte Russland seine Angriffe im Ukraine-Krieg deutlich erhöht – jedoch ohne wirklich nennenswerte Erfolge. Vor allem rund um die Region Bachmut erlitten die Truppen massive Verluste. Unbestätigten Berichten zufolge sollen die Angreifer bis zu 500 tote Soldaten pro Tag beklagen müssen.

Hohe Verluste und kaum Panzer: Russlands Angriffskrieg kommt rund um Bachmut zum Erliegen

Auch nach Einschätzung des britischen Geheimdienstes ist der russische Angriffskrieg in der Ukraine aktuell zum Erliegen gekommen. „Dies ist vermutlich vor allem ein Ergebnis der erheblichen Verluste der russischen Kräfte“, teilte das britische Verteidigungsministerium am Samstag (25. März) mit.

Russland habe seinen Fokus nun eher auf die weiter südlich gelegene Stadt Awdijiwka und auf den Frontabschnitt bei Kreminna und Swatowe nördlich von Bachmut gerichtet. Dort wollten die Russen die Frontlinie stabilisieren, hieß es weiter. Dies deute darauf hin, dass die russischen Truppen sich allgemein wieder defensiver aufstellen würden, nachdem seit Januar Versuche einer Großoffensive keine „schlüssigen Ergebnisse“ hervorgebracht hätten.

Uralt-Panzer aus dem Museum: Russland hat im Ukraine-Krieg aktuell Nachschubproblem

Das Problem ist jedoch: Es mangelt an Nachschub – sowohl bei den Soldaten als auch bei den Waffen. So versucht der Kreml immer verzweifelter, neue Rekruten für den Ukraine-Krieg anzuwerben – unter anderem mit einem Front-Bonus. Und bei den Panzern müssen Putins Truppen aktuell bereits auf Uralt-Panzer aus dem Museum zugreifen.

Im Kreml bleiben die Probleme nicht verborgen. So erhöhte Medwedew, der mittlerweile Vize-Chef des Nationalen Sicherheitsrates ist und als Putin-Freund immer wieder Drohungen gen Westen schickt, den Druck auf die Waffenfabrikanten. Vor Vertretern einer nationalen Rüstungskommission forderte er mehr Tempo in der Produktion ein – und drohte zugleich den Industriellen.

Zitat von Stalin: Medwedew droht Rüstungsindustrie mit Konsequenzen

In einem von ihm selber veröffentlichten Video sitzt er an einem langen Tisch vor den Sitzungsteilnehmern und liest dabei aus einem Telegramm vor, das der gefürchtete Sowjetdiktator Josef Stalin einst an seine Waffenfabrikanten verschickte. „Sollte sich in ein paar Tagen herausstellen, dass Sie Ihre Pflicht gegenüber dem Vaterland verletzen, so werde ich damit beginnen, Sie wie Verbrecher zu zerschlagen“, zitiert Medwedew aus dem Schreiben aus dem Jahr 1941 und fügt dann hinzu: „Kollegen, ich will, dass Sie mir zuhören und sich an die Worte des Generalissimus erinnern.“

Panzer, Drohnen, Luftabwehr: Waffen für die Ukraine

Doch ein wenig Gnadenfrist bleibt der russischen Rüstungsindustrie vielleicht noch. So wiegelte der ukrainische Präsident Wolodymyr Selenskyj die Berichte über eine mögliche ukrainische Gegenoffensive ab. Derzeit sei man noch nicht so weit, sagte er in seiner abendlichen Videoansprache am Freitag. Kiew warte derzeit noch auf wichtige westliche Waffen, darunter Panzer, Artillerie und das Mehrfachraketenwerfer-Artilleriesystem MLRS. Angaben, wann er mit der Lieferung aus den USA rechnet, machte er aber nicht. (jkf/dpa)

Während Putin- Russland versucht Belarus näher an sich zu binden, mit Nachschubschwierigkeiten und Rüstungsproduktion und Truppenerosion hadert und in der Ukraine beschäftigt ist, der neue MSC- Chef Heusgen Russland als „nur noch eine Tankstelle Chinas“ bezeichnete, versucht nun China seinen Einfluss auf Kosten Russlands in Zentralasien auszubauen, weswegen Xi nun einen eigenen China- Zentralasien- Gipfel abhält. Zumal sich viele zentralasiatische Staaten des postsowjetischen Nahen Auslands sich nach der Ukraineinvasion Putins potentiell mittel- und langfristig auch selbst bedroht sehen, sollte Russland wieder erstarken, zudem sie auch noch russische Minderheite haben und Putin in der Vergangenheit auch schon mal deren Souveränitat und territoriale Integrität infrage gestellt hatte.

“Xi snubbed Putin after their summit, calling a meeting of Central Asian countries as part of an audacious power play

- China’s leader, Xi Jinping, has made a power move timed with his visit to Russia.

- He set up a new meeting of Central Asian countries the week, muscling in on Russia’s backyard.

- The Kremlin has long seen former-Soviet republics as part of its sphere of influence.

China’s leader, Xi Jinping, has called a meeting of former-Soviet Central Asian countries, in an audacious power play in Russia’s backyard the week of his summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Xi invited the leaders of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan to the first China-Central Asia summit on Wednesday, the AFP news agency reported. It remains unclear whether the reclusive state of Turkmenistan has been invited.

The states are all former members of the Soviet Union, and Moscow has long regarded them as being in its sphere of influence after the then-Russian Empire conquered them in the 19th century.

The move came as Xi was visiting Putin in Moscow as part of a 3-day-summit which concluded Wednesday, in which the nations pledged to deepen and extend their cooperation — and Xi signaled that Russia would have continued Chinese backing in its invasion of Ukraine.

Analysts say that China has secured significant leverage over Russia in return for its diplomatic and economic support, and that in calling the meeting of Central Asian nations it is seeking to exploit that advantage.

—Carl Bildt (@carlbildt) March 22, 2023

„I’m not sure this China initiate is greeted with enthusiasm in the Kremlin,“ tweeted Carl Bildt, the cochair of the European Council on Foreign Relations.

„Agree. i’m also not sure the Kremlin has much they can do about it,“ replied Ian Bremmer, a political scientist and founder of the Eurasia Group.

Russia in launching its invasion of Ukraine last year sought to regain its control over the former Soviet state, which in recent years sought closer ties with the West.

But the invasion has stalled, amid steep military losses for Russia, and a knock-on effect has been that the former Soviet states in Central Asia have become increasingly open in their defiance of the Kremlin.

In one striking example, Kazakhstan’s President, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, declined to recognize the legitimacy claims by pro-Russian separatists in east Ukraine while sharing a stage with Putin at an economic forum in St Petersburg.

China in recent years has increased its economic and security ties with Central Asian nations, which have abundant mineral resources and lie on ancient trade routes between east and west.

Die VR China verdrängt jetzt Russland aus Zentralasien, trotz SCO. Nebenbei bauen sie jetzt eigene private Sicherheitsunternehmen auf nach dem Vorbild von MPRI, Blackwater und Wagner, da chinesischer VBA-Truppen noch nicht so offen und gerne in diesen Staaten gesehen werden. Bleibt abzuwarten ,ob es auch mal in Zukunft einen US-CAS oder EU-CAS-Gipfel geben wird, Global Gateway und B3W und NATO Partnershop Programms in Zentralasien stattfinden werden. Aber ich glaube eher nicht, zumal die VR China da mit ihrer Neuen Seidenstraße und der SCO schon Wurzeln geschlagen hat. Zudem der Westen und die NATO nach dem Afghanistanfiasko wohl auch die Schnauze vor weiteren abenteuerlichen Hasardeureinsätzen haben.

Laut ntv soll Putin erklärt haben,dass er kein Militärbündnis mit China wolle. Soll man das glauben,will er den Westen nur beruhigen oder wollen die Chinesen das selbt nicht oder ist Putin sauer,dass Xi gleich nach dem Moskau-Besuch ohne ihn zu fragen einen China-CAS-Gipfel ohne ihn abhält? Der Vater des russischen Asian Pivot Karaganow dürfte nun in einigen Erklärungsschwierigkeiten sein.

„NATO plant neue „Achse“ Putin: „Gehen kein Militärbündnis mit China ein“

Der Westen ist besorgt, dass China mit Rüstungslieferungen die russische Invasion in der Ukraine unterstützen könnte. Kremlchef Putin sagt nun, dass eine Zusammenarbeit gebe, aber kein Bündnis. Seinen Auftritt im TV nutzt er zudem einmal mehr für Attacken auf die NATO und krude Geschichtsvergleiche.

Russland und China schmieden nach den Worten des russischen Präsidenten Wladimir Putin trotz engerer Zusammenarbeit kein Militärbündnis. Die Kooperation ihrer Streitkräfte sei transparent, sagte Putin in einer am heutigen Sonntag ausgestrahlten Stellungnahme im Staatsfernsehen. Wenige Tage zuvor hatten Putin und der chinesische Präsident Xi Jinping bei dessen Moskau-Besuch die Freundschaft ihrer beiden Staaten bekräftigt. Sie hatten zudem erklärt, sie strebten engere Beziehungen an – auch im militärischen Bereich. Putin äußerte sich einen Tag, nachdem er die Stationierung russischer taktischer Atomwaffen in Belarus angekündigt hatte.

„Wir gehen kein Militärbündnis mit China ein“, sagte der 70-Jährige nun im Staatsfernsehen. „Ja, wir haben eine Zusammenarbeit im Bereich der militärisch-technischen Interaktion. Wir verbergen das nicht. Alles ist transparent, es gibt nichts Geheimnisvolles.“ Bereits Anfang 2022 – kurz vor Beginn des russischen Angriffs auf die Ukraine – hatten Russland und China eine Partnerschaft ohne Grenzen beschlossen.

China hat anders als zahlreiche westliche Staaten die russische Invasion nicht öffentlich angeprangert. Die USA haben die Besorgnis geäußert, dass China Russland mit Waffen versorgen könnte. Die Führung in Peking weist dies zurück.

Ansichten „eifersüchtiger Menschen“

Putin bestritt, dass die engeren Beziehungen zur Volksrepublik in den Bereichen Energie und Finanzen zu einer übermäßigen Abhängigkeit Russlands von China führen würden. Das seien die Ansichten „eifersüchtiger Menschen“, sagte Putin dazu. „Seit Jahrzehnten wünschen sich viele, China gegen die Sowjetunion und Russland aufzubringen und umgekehrt“, sagte er. „Wir begreifen die Welt, in der wir leben. Wir schätzen unsere gegenseitigen Beziehungen und das Niveau, das sie in den vergangenen Jahren erreicht haben, sehr.“

Zugleich warf der russische Präsident den USA und dem von ihnen geführten Militärbündnis NATO vor, eine neue globale „Achse“ aufzubauen. Putin nannte Australien, Neuseeland und Südkorea als Kandidaten für einen Beitritt zu einer „globalen NATO“ und verwies auf ein Anfang des Jahres von Großbritannien und Japan unterzeichnetes Verteidigungsabkommen. „Deshalb sprechen westliche Analysten davon, dass der Westen beginnt, eine neue Achse aufzubauen, ähnlich derjenigen, die in den 1930er-Jahren von den faschistischen Regimen Deutschlands und Italiens und dem militaristischen Japan geschaffen wurde“, sagte Putin.

NATO-Generalsekretär Jens Stoltenberg hat dieses Jahr Japan und Südkorea besucht und die Bedeutung der engen Zusammenarbeit des Militärbündnisses mit Partnern im indo-pazifischen Raum unterstrichen. Er hat auch von zunehmenden Spannungen zwischen dem Westen und China gesprochen und mehr militärische Unterstützung für die Ukraine gefordert.

Chinaexperte Professor van Ess kommentierte dazu noch:

„Mit der Aussage schützt Putin China natürlich auch vor westlichen Sanktionen. Aber über die Grenze zwischen China und der UdSSR in Kasachstan war natürlich Gegenstand langjährigen Streits bis 1989, denn die Chinesen sind der Auffassung, dass die Qing-Dynastie das Gebiet bis zum Balchaschsee beherrschte. Zigtausend Quadratkilometer, wenn auch meistens wüstenartige Steppe.“

Kurz, zackig und knackig brachte es auch noch Ex- NATO- General Domroese jr. auf den Punkt:

„Xi weiß, warum… er will sich nicht unnötig vertraglich binden mit einem loser.“

Interessant auch noch ein Beitrag der Jamestown Foundation über Chinas Private Security Companies in Zentralasien:

The Role of PSCs in Securing Chinese Interests in Central Asia: The Current Situation and Future Prospects

By: Sergey Sukhankin

February 22, 2023 01:25 PM Age: 1 month

Executive Summary

- Despite China`s growing presence—especially in the realms of business and trade—in Central Asia, anti-Chinese sentiments and the overall level of suspicion toward Beijing have been on the rise. Frequently, this leads to public protests that sometimes result in instances of violence. To protect its nationals and property, China is considering the increased use of private security companies (PSCs). On some occasions, the employment of these companies within Central Asia have been confirmed. In the future, China will most likely increase its reliance on these actors.

- Due to economic dependency and an exorbitant level of indebtedness, two main candidates for hosting or increasing the level of engagement with Chinese PSCs are Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, though other countries should not be ruled out.

- While China might attempt to increase the use of its PSCs in Central Asia, multiple risks are associated with this approach, including the danger of growing Sinophobia and anti-Chinese protests.

- As of today, Chinese PSCs in Central Asia should be viewed as being more of a “continuation of business by other means” rather than military-political tools or instruments of geopolitical competition.

Central Asia plays a vital role for China’s growing economic, business and geopolitical ambitions. In addition to the region’s abundance of essential natural resources, such as hydrocarbons and rare earth minerals, Central Asia is situated in a strategic geographic location, securing Beijing’s direct access to the European and Middle Eastern markets and their resources. Yet, despite its resource wealth and strategic location, as well as China’s growing business presence, challenges abound with Beijing’s ambitious plans for the region. On one hand, the outbreak of violence in the Middle East following the Arab Spring has become a destabilizing factor that has negatively affected the greater Middle East region. Given the relatively low living standards, high levels of unemployment across Central Asia and the region’s geographic proximity to local hotspots, radicalization has penetrated the region, posing a serious challenge to both local regimes and foreign investors.

Meanwhile, China’s determination to increase its presence in the region—combined with the reported mistreatment of its own Muslim population—has resulted in growing Sinophobia, which sometimes takes hostile forms. Both these factors pose a viable challenge to Chinese plans and ambitions in the region, leading Beijing to ponder means and measures to protect its presence without exacerbating suspicion among locals. Among other measures, Beijing is considering, and in some cases employing, using private security companies (PSCs) as an instrument of tacit presence. As stated by Raffaello Pantucci in an interview[1]:

I think you are going to see China continue to push its PSCs in Central Asia. In large part because they are useful as protective security, but also because the region would be a useful testing ground for these companies going out into the world, something we have seen China do repeatedly in the region. They are also a structure that provides the Chinese state with some extra security “eyes” on the ground, which helps in all sorts of ways. I sense they might start appearing more. But at the same time, Beijing will be careful to push down discretion on the companies as there is no desire to ruffle feathers too much, and in many of these countries, there is deep resistance to Chinese (or any other foreign) PSCs.

Overall, this report will discuss China’s current and prospective use of PSCs in Central Asia, taking a country-by-country approach. In addition to using a wide pool of local and English-language sources, two interviews with world-renowned subject experts have been conducted: Raffaello Pantucci, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies and senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute,[2] and Temur Umarov, a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and research fellow at the OSCE Academy in Bishkek.[3]

China in Central Asia: Past and Present

Central Asia, comprising four Turkic (Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan) and one Persian-speaking (Tajikistan) former Soviet republics (with the autonomous Chinese region of Xinjiang and Afghanistan also sometimes included[4]), has played an instrumental role in China`s trade and geo-economic initiatives. For instance, the region was the key pillar of the ancient Silk Road trade route.[5] However, following a series of historic events, including the outbreak of the bubonic plague in 542 CE that shook the Byzantine Empire; the weakening of China in the late 9th century; the Mongolian invasion in 1216–1221; and the beginning of the Age of Discovery in the 15th century, Central Asia came to forfeit its role as a key commercial transit route.[6]

Later, with Russia`s conquest of Central Asia in the 18th and 19th centuries and its subsequent incorporation into the Soviet Union in 1924, the region forfeited its sovereignty, remaining under Moscow’s thumb until 1991. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia lost its exclusive right as sole stakeholder in the region, while the role of other actors, such as Turkey, Iran, the United States and, perhaps most notably, China, became much more prominent. Importantly, throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Beijing included Central Asian countries in two of its major strategic initiatives aimed at dramatically increasing China’s foreign economic presence and revitalizing its economically underdeveloped regions—one being the “Go Out” policy (走出去战略) and the other the China Western Development strategy (西部大開發).[7] These initiatives placed high importance on Central Asia due to its role as a key logistical route and as a factor for domestic security and stability.

Unlike other foreign actors, whose policies either did not fully consider local cultural specificities, as was the case for the West, or took a dismissive, and to some extent pejorative, approach, such as Russia, China’s strategy is distinctly different. This approach is premised on three main pillars: (1) not interfering in the region’s internal affairs and relations between countries in the region; (2) fully concentrating on economic cooperation; and (3) relying on the promotion of Chinese soft power as a propaganda tool to build a positive image of China.

Yet, despite the benign image Beijing has attempted to create for itself, Chinese policies in Central Asia have drawn criticism from the European Union and to a much greater extent the US, whose leadership accuse China of multiple transgressions, including the use of so-called “debt trap” diplomacy; violating key principles of environmental and social sustainability; fostering corruption and bad local governance through the construction of political vanity projects and kickback schemes; objectionable security cooperation practices; and Beijing’s handling of the “Xinjiang problem.”[8] Importantly, within the countries of the regions themselves, despite massive economic investment and a relatively flexible approach, Chinese policies sparked the rapid growth of anti-Chinese sentiment and Sinophobia accompanied by occasional sparks of violence. As a result, Beijing began to seriously consider strengthening its security presence in the region through PSCs, among other measures.[9]

The Chinese Presence in Central Asia: Key Areas

According to Temur Umarov, the Chinese presence in Central Asia could be conditionally divided into the following four main areas:[10]

- Military Presence—China has exhibited particularly strong cooperation with Tajikistan. Notably, the Tajikistani and Chinese governments signed an agreement back in 2016 to build seven border posts and training centers along Dushanbe’s border with Afghanistan. Beijing has also been deepening its military relationship with Kyrgyzstan, with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) holding its first joint military exercises with Kyrgyzstan in October 2002. In 2019, China launched a new format of military exercises, “Cooperation-2019” (协作-2019), the scope of which included exercises with Uzbekistani[11] and Kyrgyzstani paramilitaries in the Jizzakh region of Uzbekistan and in Xinjiang, respectively.[12] The strengthening of military ties between China and the countries of the region is a matter of key geopolitical importance for Beijing’s relationship with Central Asia. China’s view is perhaps best expressed in the Chinese strategic formula: “stabilize in the east, gather strength in the north, descend to the south, and advance to the west” (东稳, 北强, 南下, 西进), which perceives Central Asia to be a strategic theater for geopolitical advancement.[13] As noted by Kubanychbek Toktorbayev, a senior researcher at the National Institute for Strategic Studies of the Kyrgyz Republic, “The Chinese leadership quickly realized that the Central Asian region would play the role of a ‘strategic home front’ [for China]. … Beijing has recognized the importance of Central Asia as a resource provider for the Chinese economy.”[14]

- Trade and Import of Natural Resources (Primarily Hydrocarbons)—This has remained China`s key priority. However, rare earth minerals and metals constitute another branch of Chinese economic interests. For example, China imports 21 percent of its zinc and more than 20 percent of its lead from Central Asia. Meanwhile, China is strategically interested in exporting its goods with high-added value to the region. For instance, Chinese cameras and surveillance systems have been actively imported across the region.[15] Overall, for the past 30 years, trade between China and Central Asian countries has grown by more than 100 fold.[16]

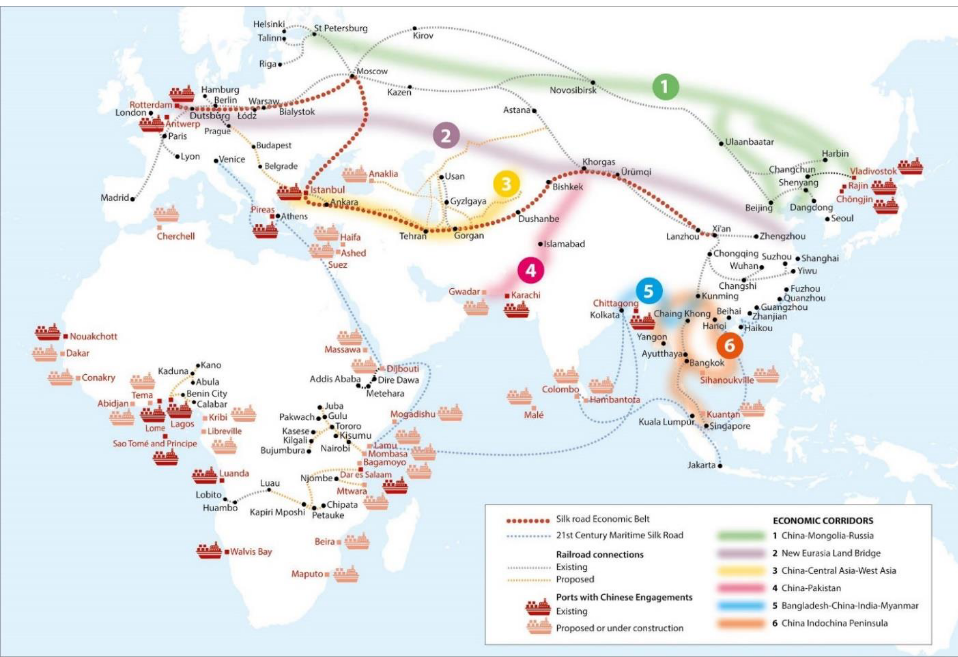

- Investments—According to Chinese sources, regional investments have experienced major growth. By 2020, total Chinese investment in Central Asia had reached $40 billion. By various estimates, almost half of this sum went to Kazakhstan.[17] About 7,700 Chinese firms were reported to be operating in the region by the end of 2021.[18] Importantly, in terms of trade, logistics and investment, China’s strategy is inseparable from its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Demonstrating the region’s importance to the project, its inception was officially proclaimed in 2013 in Astana. Specifically, the China–Central Asia–West Asia Economic Corridor (CCAWAEC), which links China with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran and Turkey, exemplifies the region’s importance. Moreover, the Chinese side aims to connect domestic producers with European markets through a complex network of highways and railways running through Central Asia. Out of six proposed mega transportation arteries that are to form the land-based part of the BRI, namely the New Eurasian Land Bridge, the China–Mongolia–Russia Economic Corridor,[19] the aforementioned CCAWAEC, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor and the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor, Central Asia plays a crucial role in four of them.

- Soft Power—China strives to promote its soft power in the region through several channels. For instance, as demonsrated by Umarov, between 2000 and 2017, Chinese governmental representatives paid official visits to Central Asia on 722 occasions. Moreover, Chinese experts, such as Justin Yifu Lin, have been recruited as government advisors. China has been quite active in promoting its culture and projecting influence via the Confucius Institute network, with a total of 37 branches being opened in Central Asia. China has also actively provided study grants for the most-talented students from the region, especially in the realms of information technology and new technologies.[20] The strategic importance of the region is highlighted not only by the attention given to it by Chinese government agencies but also by the existence of more than 30 large research institutions—including those under the umbrella of China’s largest and most reputable universities—specifically tasked with researching and monitoring developments in Central Asia.[21]

Figure 1. China’s Belt and Road Initiative  Source: OECD. Source: OECD. |

China’s Concerns in Cooperating With Regional Actors

Despite massive economic investments and growing trade networks, China has faced multiple risks and challenges in Central Asia. To begin with, Beijing has had to deal with a growing negative image in the region. As demonstrated by the recent Central Asia Barometer Survey, a biannual large-scale research project that measures social, economic and political atmospheres in Central Asia, the perception of China in the region is becoming increasingly negative.[22] As a result, Sinophobia has been rapidly spreading in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan.[23] In part, this results from routine conflicts between Chinese nationals and locals that stem from inequalities such as pay conditions, unequal treatment and instances of abuse found within Chinese-owned businesses. While this is by no means a new phenomenon,[24] these tendencies have increased so much so that some local sources called 2019 “the year of anti-Chinese moods in Kazakhstan.”[25]

Another reason for growing Sinophobia is linked to developments in Xinjiang. In addition to its ethnically Turkic Uyghur population, Xinjiang is home to ethnic Kazakhs (1.5 million), Kyrgyz (180,000), Tajiks (5,000) and Uzbeks (10,000). Revelations about Xinjiang’s massive network of labor camps for Muslims[26] have triggered protests in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, accompanied by demands to rid these countries of Chinese influence. Furthermore, anti-Chinese feelings accompanied by protests have also grown as a result of corruption in the border control areas, of which local Kyrgyzstani and Kazakhstani authorities have been implicated in corruption-related scandals involving document forgery and bribery connected to China.[27]

In addition, worsening security-related challenges, such as the growing potential for conflict[28] and the growing threat of terrorism, pose a range of complications for China. Growing security issues have led some in Beijing to express concerns about Central Asia potentially becoming a base of support for the so-called “Three Evils” (or “Three Forces”; 三股势力) of terrorism, separatism and extremism. Chinese media and officials have identified terrorist organizations and religious extremists operating in Central Asian states (e.g., the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, Jamaat Ansarullah and Islamic Jihad Union) as threats to Chinese nationals both inside and beyond China.[29] To address these challenges, between 2015 and 2020, Beijing made significant investments in security in Central Asia, expanding its share of arms deliveries within the region to 18 percent. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has also strengthened security coordination measures with Central Asian countries at the regional level.[30]

With that being said, however, joint training and arms supplies might have limited applicability given the frequently non-conventional nature of threats faced by China in the region. For this purpose, in addition to more conventional traditional measures, the PRC is also considering alternative ways to protect Chinese BRI investments in Asia that include the greater use of PSCs.[31]

China’s Security Cooperation With Select Actors: Prospects for the Use of PSCs

Kazakhstan

Given its size, geography and economic potential, Kazakhstan occupies a key position in the Central Asian segment of the BRI. However, China is currently facing two main challenges in the country. First is the threat posed by Islamic radicals and their potential ties to ethnic minorities such as the Uyghurs. According to Human Rights Watch, in 2019 alone, the Kazakhstani authorities detained 500 alleged members of the Islamic State and their families and sentenced 14 citizens for their participation in conflicts in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan.[32]

The second major concern is the spread Sinophobic tendencies within Kazakhstan. As noted by political commentator Dosym Satpayev, “Kazakhstan is the only Central Asian country that has always had anti-Chinese sentiments.”[33] Anti-Chinese sentiments in 2019 culminated with demonstrations in the western oil-producing city of Zhanaozen. Anti-Chinese demonstrations have sometimes grown openly hostile, especially in the western part of Kazakhstan around the North Troyes oilfield and the town of Atyrau.[34] One 2019 conflict triggered by a payment dispute between locals and Chinese workers resulted in a harsh, first-of-its-kind warning – when a Chinese official harshly criticized local protestors and implicitly made a point about inaction of the local authorities – by Geng Liping (耿丽萍), the PRC’s consul general in Almaty. Local sources construed this as a sign of Beijing’s growing dominance in the country, believing that it could potentially result in “[Chinese] police or security forces [deployed to Kazakhstan] under the pretext of protecting Chinese private property.”[35]

To address these challenges, the PRC relies on two main mechanisms. First, 16 joint anti-terror military exercises between China and Kazakhstan have been conducted since 2002.[36] The drills in 2019 included the use of unmanned aerial vehicles to detect, round up and destroy hypothetical terrorist groups entering Kazakhstan under the guise of migrant workers from the territory of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.[37] As part of its anti-terrorism policies, Beijing is also actively promoting the intensification of academic exchanges and knowledge transfers, building a steady link between Chinese and Kazakhstani military academies and institutions.[38]

The second mechanism involves arms deals and military aid. Chinese arms deals with Kazakhstan deserve attention for two key reasons. To begin with, the bilateral relationship between Beijing and Astana has allowed Kazakhstan to acquire increasingly sophisticated weapons systems. For example, in 2016, China supplied a number of Wing Loong-1 (翼龙-1) strike-capable drones, comparable to the US-manufactured MQ-1 Predator.[39] Furthermore, the PRC appears to have supplanted Russia as Kazakhstan’s primary arms supplier, and this trend is likely to grow in the future. China is supplying the Kazakhstani military with platforms analogous to models produced in Russia and the Soviet Union, such as the Y-8 (运-8) transport aircraft, a copy of the Antonov An-12.[40] These two factors demonstrate differences in Chinese military aid to Kazakhstan, in contrast with the nature of Beijing’s aid to Tajikistan or Kyrgyzstan. Military sales and assistance in the latter two countries, such as the transfer of 30 heavy trucks,[41] plays a less significant role in the development of bilateral relations.

However, beyond these two primary mechanisms, a third alternative path could include the employment of PSCs by Beijing. Importantly, some of China’s paramilitary state organizations, such as the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (新疆生产建设兵团), are already reorienting their services toward serving the needs of the BRI. Local sources in Kazakhstan have also speculated about the potential deployment of Chinese PSCs in the country, such as the Hong Kong-based Frontier Services Group (先丰服务集团).[42] This is a sensitive issue, given the reality of growing weariness toward China alongside the expanding presence of Chinese businesses in the countries. Leading Kazakhstani politicians, including Dariga Nazarbayeva, have voiced categorical disapproval of any PSCs, either foreign or domestic, operating in the country.[43]

Temur Umarov, meanwhile, stated in an interview that, in its attempts to employ PSCs on Kazakhstani territory, China may encounter a fundamental challenge. Kazakhstan (along with Kyrgyzstan) is one of two countries in Central Asia where public discontent is best heard. Thus, the use of PSCs would become audible instantly and might trigger a wave of discontent and further escalation of Sinophobia. As noted by Rafaello Pantucci, even though the obvious candidates for the use of PSCs within the region are Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, “I think you will also see them appearing in Kazakhstan as it is an environment where there is a friendly government that they can work with, and it therefore provides an environment where these companies can start to learn their trade in a foreign, relatively secure, environment. Most of the clashes they would be dealing with would be among workers which should be easier clashes to resolve.”

Uzbekistan

The Uzbekistani government, which has seemingly embarked on a more reformist path after the 2016 death of long-time leader Islam Karimov and subsequent election of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, has viewed the BRI and cooperation with China as a chance to become an integral part of the CCAWAEC. Tashkent’s aspirations in this regard have been welcomed by Beijing, with the Chinese state-managed Silk Road Fund (丝路基金) agreeing to provide Uzbekistani state-owned oil and gas corporation JSC Uzbekneftegaz with a $585 million loan.[44] Similarly, the PRC-dominated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (亚洲基础设施投资银) declared its readiness to grant a $165.5 million loan (81 percent of the total cost) to pay for the Bukhara Road Network Improvement Project, to be completed by 2025.[45]

The main threat to Chinese investors in Uzbekistan comes primarily from the activities of violent jihadists, many of whom have gained international experience fighting in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan. For instance, the Taliban, since taking control of the Afghan government in 2021, has carried out operations near the shared Afghan-Uzbekistani border.[46] A network of Hizb ut-Tahrir, which had known cells in five different parts of the country, was reportedly uncovered in the Fergana region of eastern Uzbekistan.[47]

Similar to Kazakhstan, China relies on a few main instruments to deal with this challenge, in addition to the use of PSCs. First, joint military exercises have recently begun to occur between Beijing and Tashkent. In December 2017, discussions between then–Chinese Minister of Defense Chang Wanquan, then-Uzbekistani Minister of Defense Abdusalom Azizov and President Mirziyoyev produced agreements for closer security cooperation. This culminated in the emergence of “Cooperation-2019” (合作-2019), a joint anti-terrorism exercise between the Chinese People’s Armed Police (中国人民武装警察部队) and the Uzbekistani National Guard, which took place in May 2019.[48] According to PLA exercise commander Wang Ning, China views Uzbekistan as “an important strategic partner” in achieving peace and stability in Central Asia.[49]

Second, while Uzbekistan is not a top priority for China in terms of arms exports, some notable changes have taken place since 2014, when Uzbekistan became the first Central Asian state to acquire the PRC-manufactured Wing Loong I drone.[50] Later, it was reported that Uzbekistan allegedly acquired an unnamed number of Pterosaur I drones, a variant of the Wing Loong.[51] Subsequently, Tashkent purchased and successfully tested the FT-2000, an export version of the Hongqi-9 (紅旗-9), which is similar to the Russian S-300 surface-to-air missile system.[52] The most recent Chinese weaponry acquired and tested by the Uzbekistani Armed Forces was the QW-18 (前卫-18) shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missile system, which entered Uzbekistan’s inventory in 2019.[53]

Third, China has established non-standard forms of cooperation with PSCs, represented by the China Security Technology Group (中国安保技术集团) already offering services in Uzbekistan, albeit without an official local office.[54] The Frontier Services Group has also announced plans to deploy in Uzbekistan due to the country’s growing involvement in the BRI,[55] and it is likely that PSCs will continue to expand their operations there. The majority of Uzbekistani policymakers, similar to their Kazakhstani counterparts, frown upon the idea of Chinese private security personnel operating in Uzbekistan. Given Uzbekistan’s growing economic dependence on BRI-related initiatives and its acute need for foreign investment, this position may be subject to change in the future.

Additionally, military journalism and propaganda plays a key role in the Sino-Uzbekistani military partnership. In 2019, a delegation from the Uzbekistani Defense Ministry visited the PRC to study organizational and operative principles of the Chinese military media. During the trip, the delegation visited the head office of the People’s Daily and the School of Journalism at the Renmin University of China.[56] Reflecting on the use of PSCs in Uzbekistan, Temur Umarov stated that, for China, this prospect could be limited. He added that, despite recent political changes, Uzbekistan remains a police state, where militia and security services are able to control various aspects of public life. Thus, the use of foreign PSCs, given the relatively stable domestic security environment, is by and large redundant.

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan has a policy of state neutrality, which for decades has kept it in isolation under the helm of its extravagant leadership and beset by problems of ethnic nationalism. At the same time, it has hoped to occupy a leading role in the BRI and reap benefits from Chinese economic investments. An October 2017 book written by then-President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov—filled with legends, historical descriptions and local folklore and titled Turkmenistan is the Heart of the Great Silk Road[57]—underscored these high aspirations. Turkmenistani authorities have primarily vested their BRI hopes in two major infrastructure projects: The China–Kazakhstan–Turkmenistan–Iran Railway and the Turkmenbashi International Seaport (completed in 2018), which links Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan (Baku), Kazakhstan (Aktau) and Russia (Astrakhan). The port serves as an integral part of the Lapis Lazuli Corridor, facilitating the transportation of goods between Central Asia and the Persian Gulf.[58]

Although the PRC’s ties with Turkmenistan are not as close as those with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, Beijing has increased both economic and security-related contacts with Ashgabat in recent years. Chinese military experts have always viewed Turkmenistan as a weak state in terms of military capabilities.[59] This year, China overcame Russia to become the second-largest arms supplier to Turkmenistan by selling weaponry in return for natural gas payments. China has monopolized exports of Turkmenistani natural gas to such an extent that gas has been used as a de facto form of currency in economic contacts between the two countries.

China now supplies 27 percent of Turkmenistan’s foreign arms purchases, behind only Turkey.[60] Between 2016 and 2018, Turkmenistan acquired HQ-9, Kai Shan-1 (凯山-1) and FD-2000 missiles from China.[61] However, cooperation was strained in 2018 when the price of natural gas on the Chinese market skyrocketed. An ensuring disagreement resulted in China blacklisting Turkmenistan and putting a de facto temporary ban on all major types of security-related cooperation. Later, in the final months of Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov’s leadership and the subsequent accession of his son Serdar (in power since March 19, 2022), relations with China started to change.

In November 2021, Turkmenistan (represented by Serdar Berdimuhamedov) and China signed agreements in the political, diplomatic, trade, economic, cultural and humanitarian spheres.[62] The Chinese side argued the need to “elevate China-Turkmenistan cooperation to a new level to bring more benefits to the two countries and peoples” and mentioned that “the two countries should make progress in energy cooperation and jointly forge a strategic energy partnership that covers the entire industrial chain.” Of particular importance was an allusion by the Chinese officials to the fact that “the two countries should enhance political mutual trust and jointly safeguard the security and stability of the two countries and the region.”[63] Given the fact that Turkmenistan is rapidly becoming a “regional energy powerhouse”[64] that aims to double natural gas exports to China[65] (a development that became clear after Ashgabat and Beijing reached an agreement on developing the second stage of the Galkynysh gas field in southeast Turkmenistan[66]), cooperation between the two countries will be additionally strengthened.

Finally, it needs to be mentioned that, during the meeting between Serdar Berdimuhamedov and Chinese President Xi Jinping, the Chinese side confirmed its readiness to strengthen cooperation with Turkmenistan within the “China+Central Asia” mechanism, paying special attention to the implementation of the Global Development Initiative and Global Security Initiative,[67] which may result in the strengthening and additional enhancement of security ties between the two countries.

Tajikistan

Chinese interests in Tajikistan are primarily based on two interrelated elements. The first is related to geo-economic calculations, in which Tajikistan is viewed as an essential part of the “Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism,” a framework established in 2016 consisting of China, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan. This arrangement was intended to grant China access to the Indian Ocean.[68] The second element involves security-related concerns, which Beijing sees as connected to the aforementioned “Three Evils.” As such, Tajikistan occupies a key buffer region for China and is seen as an integral part of resolving these concerns.[69]

In June 2019, Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping and Tajikistani President Emomali Rahmon agreed to further deepen the two countries’ “comprehensive strategic partnership,” which included strengthening bilateral cooperation “in combating the ‘Three Forces’… as well as transnational organized crimes [and] cyber security.”[70] Chinese concerns related to the situation in Tajikistan, and potential repercussions for the BRI, have been amplified by reports that around 400 militants—associated with ISIS, Jamaat Ansarullah and the Turkistan Islamic Movement—have attempted to establish a new terrorist base on the territory of the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) in the country’s east, along the border with China.[71]

To effectively deal with these challenges, Beijing is relying on four main pillars. The first of these is fortifying Tajikistan’s physical security infrastructure. The logic of creating military infrastructure in Tajikistan has been summarized by Beijing-based military expert Li Jie, who noted that, if Chinese forces wish to “eliminate the so-called ‘Three Forces,’ they need to go to their bases of power and take them down. But since the PLA is not familiar with the terrain … bilateral cooperation is the best way to get win-win results.”[72] The foundation for this policy was set in October 2016, when Beijing and Dushanbe reached an agreement on modernizing security infrastructure in their border regions, which reportedly included plans for 11 “outposts of different sizes” and a training center for border guards.[73]

The second pillar is the direct presence of Chinese forces in the country. Tajikistani authorities have repeatedly denied rumors regarding the existence of Chinese military bases in the country.[74] However, in the Murghob District of the GBAO, a Chinese military base (officially a Tajikistani base built to protect Chinese investments) has been operating there for at least four years.[75] Locals have claimed that several hundred Chinese soldiers have been deployed at the base.[76] Further investigations have revealed that the “Chinese soldiers” are in fact representatives of the Chinese People’s Armed Police (中国人民武装警察部队), or PAP.

The paramilitary PAP is responsible for internal security, riot control, antiterrorism, disaster response, law enforcement and maritime rights protection,[77] operating as a rough analogue to Russia’s Rosgvardiya (National Guard). Crucially, in 2021, it was reported that the Tajikistani Interior Ministry and Chinese Public Security Ministry had reached an agreement to go ahead with the construction of a Chinese military base on its border with Afghanistan in the GBAO “to boost regional security.” According to the report, the new base will be owned and operated by Tajikistan’s special forces, the Rapid Reaction Group, with the estimated $10 million in costs financed by China.[78] As noted by Tajik political scientist Parvis Mullojonov in a related comment,

China has a strategic vision. The possibility that it could use these bases for its army in the future cannot be ruled out. For the time being, however, these border posts are there for Afghanistan. … China’s political interests in neighboring countries are the reason why it strives to secure its investments.[79]

Incidentally, Temur Umarov noted in an interview with this author that to protect its interests in the country, China is likely to opt for “power bases.” He noted that talks have progressed on the prospective deployment of between seven to 11 such bases in the country, instead of the direct use of PSCs.[80]

The third of Beijing’s pillars of cooperation with Dushanbe consists of training and military support, which is intended to serve a dual purpose. In addition to dealing with Islamic militants, it also increases China’s influence in the country. Given the state of Tajikistan’s economy and the near-complete collapse of its armed forces and defense industry after 1991, this is especially true. According to local analysts and military experts, Tajikistani military capabilities are still inadequate for the range of challenges faced by the country and therefore require foreign assistance.[81] The intensification of Chinese-Tajikistani military cooperation reached another landmark in 2016, when combined military exercises involving 10,000 men were held in the Pamirs region in the Ishkashim district of the GBAO.[82] A three-day military exercise was repeated in the same area in 2019,[83] which led some international observers to comment that Dushanbe was “increasingly outsourcing its security needs to Beijing.”[84] Furthermore, among the Central Asian states, Tajikistan is the largest recipient of uncompensated Chinese military aid, which now also extends to the construction of military facilities and apartments for Tajikistani military officers.[85]

The fourth Chinese pillar for increasing security (and influence) in Tajikistan is the use of PSCs, a phenomenon likely to grow in significance as China’s BRI projects continue to expand throughout the region. As noted by Lu Guiqing, general manager of the Zhongnan Group, “When you ‘go out,’ safety is the most important.”[86] While there is no firm evidence to indicate that Chinese PSCs are currently operating in Tajikistan, analysis of the Chinese PSC industry points to China Overseas Security Group (中国海外保安集团) and Frontier Services Group as the enterprises best suited for deployment to the country.[87]

In light of a controversial 2011 agreement that reportedly put 1 percent of Tajikistani territory under de facto PRC control, as well as the huge debts owed by Dushanbe, Beijing has significant opportunities to boost its military and paramilitary presence in the country. These opportunities in turn will open up valuable inroads to Afghanistan.[88]

Kyrgyzstan

The range of challenges faced by China in Kyrgyzstan is similar to those found in Tajikistan, with the prospects of terrorism and public unrest being the two main challenges faced in the country. In addition, one must mention anti-Chinese sentiment, which is sometimes accompanied by violence.[89] The incident with arguably the greatest impact on Chinese security perceptions in Kyrgyzstan was the 2016 terrorist attack on the Chinese embassy in Bishkek, which vividly exposed the weaknesses of the Kyrgyzstani security system. As noted at the time by Li Lifan of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, “The attack will almost certainly have security implications for many Chinese projects in Kyrgyzstan and other Central Asian nations as they become the new linchpin of the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative.” Another commentator, Li Wei of the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, predicted that security conditions would worsen “due to collusion between local fundamentalist movements and the exiled Uyghur Muslim extremist groups.”[90]

To deal with these challenges, the Chinese side is likely to rely on two main tools. The first of these consists of exercises and military aid to boost local security capabilities, which were seriously weakened after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Similar to a parallel effort in Tajikistan, the PRC has sponsored an aid program for the construction of apartments for local military officers.[91] The first combined Sino-Kyrgyzstani anti-terrorism exercises were launched in October 2002 near their shared border at the Irkeshtam crossing and involved Kyrgyzstan’s border forces and approximately 300 Chinese troops from Xinjiang.[92]

Later, anti-terrorism training for the Kyrgyzstani Armed Forces was placed primarily under the framework of the Russian-dominated Collective Security Treaty Organization. However, Beijing has maintained a significant role, with ten joint Kyrgyzstani-Chinese training exercises and events being held between 2003 and 2016, and this has been accompanied by the growth of Chinese military aid.[93] A critical milestone was reached in 2019, when a bilateral counterterrorism exercise titled “Cooperation-2019” was launched at a training base in the Xinjiang region, involving members of the PAP and the National Guard of Kyrgyzstan.[94]

Furthermore, the Chinese are likely to employ and put PSCs to test in Kyrgyzstan.[95] Given the lower level of risk in Kyrgyzstan as compared to neighboring Tajikistan, and the general weakness of Chinese PSCs, Bishkek offers a promising testing ground for these companies. Voices arguing for the use of PSCs to protect Chinese nationals in Kyrgyzstan became louder after the outbreak of mass protests, accompanied by violence, in the centrally located Naryn region.[96] These incidents revealed explicit anti-Chinese sentiment and vividly demonstrated difficulties that Chinese businesses have had with protecting their employees and property.[97] In addition to a harsh official statement issued by PRC officials that demanded improved security for Chinese nationals in the country, Chinese businesses have unofficially asked for permission to employ PSCs.[98]

Local commentator Mederbek Korganbayev has written that “in the future China might be able to lobby— through the Kyrgyz Parliament—for a law allowing Chinese investors to use PSCs on the territory of Kyrgyzstan.” The author also presumed that the personnel of Chinese PSCs will be equipped with “ordinance weapons as well as special means [spetsredstva].”[99] Kyrgyzstani officials denied these assertions, calling the article’s assertions “lies” and promising to severely punish those spreading such information.[100]

However, given overall trends, including the growing privatization of security, this prospect does not seem totally unfounded. One of the largest Chinese state-owned enterprises operating in the country, China National Electronics Import & Export Corporation, has concluded an agreement with the Kyrgyzstani government regarding public surveillance. According to local sources, cameras and other gadgets could be used by China “for protection of its interests in case of outbreaks of anti-Chinese demonstrations and provocations aimed against Chinese nationals.”[101]

According to some experts, China Railway Group, the company involved in the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan Railway project, relies on Zhongjun Junhong (中军军弘安保集团), one of the largest Chinese PSCs, which has had a branch in Kyrgyzstan since 2016.[102] This PSC has reportedly secured more than 20 Chinese clients in Kyrgyzstan. In addition to China Railway Engineering Group, these clients include Sinohydro, Huawei Technologies and Sanmenxia Luqiao Construction Group.[103]

However, speaking about the prospects of Chinese PSCs, Temur Umarov pointed to a certain duality that could direct their development within Kyrgyzstan. On the one hand, he noted that the use of PSCs in Kyrgyzstan—a country that has a track record of public protests and the undeniable readiness of the local population to openly voice its discontent with governmental policies—might prove to be somewhat challenging for China down the road. He also noted that in the event of new protests, there is no guarantee that local security and police forces would not join the protesters. At the same time, however, Umarov argued that the local political elite, an important factor in attracting Chinese capital and large infrastructural projects, may be willing to turn a blind eye to Beijing`s interest in using its PSCs within the country.

Conclusion: Prospects for China’s Use of PSCs in Central Asia

In early 2019, prominent Russian Sinologist Alexey Maslov argued that, for the time being, the PRC is experimenting with building military facilities abroad, remaining cautious of international deployments of its PSCs. However, according to Maslov, the Chinese “are not good in either element … [and only after] they have acquired the necessary skills … will it be possible to talk about full-fledged large-scale actions.”[104] That being said, more recent studies paint a more complex picture. While the total number of Chinese PSCs operating in Central Asia remains unknown, some studies suggested that, in 2021, at least six Chinese PSCs were known to be operating in the region. Information pertaining to activities of Chinese PSCs in Kyrgyzstan published by The Oxus Society analytical center is worth mentioning in this regard.[105]

Table 1. Chinese PSCs Operating in Kyrgyzstan

| Client-Company | Physical Location and Area of Responsibility | Name of Chinese PSC |

| Zijin | Taldy-Bulak (Kyrgyzstan), Gold and Copper Deposits | Zhongjun Junhong[106] (中军军弘保安服务有限公司是大功) (Specific Services Are Unknown) |

| China National Gold Corporation | Kuru-Tegerek (Kyrgyzstan), Gold and Copper Deposits | Unknown |

| Shaanxi Coal and Chemical Industry | Kara-Balta (Kyrgyzstan), Oil Refinery | Unknown |

| Xinjiang Guoji Shiye | Tokmok (Kyrgyzstan), Oil Refinery | Unknown |

| Tebian Electric Apparatus | Major Projects for Chinese Eximbank | Unknown |

| Central Asia Gas Pipeline Company (Branch of China National Petroleum Corporation) | Line D of the Central Asia–China Gas Pipeline, Trans-Tajik Gas Pipeline Company | Unknown |

| Jufeng Industry Group | Research and Exploration of Gold/Rare Earth Metals | Zhongjun Junhong |

Based on this information and previous studies, it would be reasonable to argue that the activities of Chinese PSCs in Central Asia are likely to increase, potentially covering new geographic locations and becoming more sophisticated in terms of those sectors they will be involved in. While the countries in the region and their political elite may indeed be worried about the expansion of PSCs’ operations in their countries and thus may be prone to adopting laws to curb such operations, Chinese PSCs will most likely try to use “names that conceal their real functions.”[107]

Meanwhile, two additional factors should not be downplayed. First, the aforementioned strategic and growing economic dependency on China, coupled with overarching indebtedness, make the Central Asian states increasingly dependent on China in the economic sphere. Given the growing number of large economic projects (which now extend beyond the hydrocarbon sector) and security-related challenges faced by the region, the proliferation of Chinese PSCs in the region should be expected. Second, in terms of security, the configuration of the post-1991 informal “arrangement,” by which China operates as an economic power and Russia as a security guarantor in the region, is likely to change. Moscow’s humiliating military performance in the first months of its war against Ukraine has exposed multiple weaknesses and gaps in Russia’s defense complex and security architecture. Irrespective of the outcome of the war in Ukraine, Russia’s focus will undoubtedly shift to postwar reconstruction and overcoming the imminent socioeconomic challenges posed by its growing isolation, thus leaving Central Asia off the scope of the Kremlin’s vital interests. While Russia’s presence and influence in the region has been progressively eroding since 1991, Moscow’s war against Ukraine and its accompanying developments will only accelerate this process, granting more room for maneuver to China.

Notes

[1]Raffaello Pantucci, written interview with author, November 4, 2022.

[2]Pantucci, written interview with author.

[3]Temur Umarov, video interview with author, October 19, 2022.

[4]According to many experts, “Inner Asia” includes Mongolia, Manchuria and parts of Iran.

[5]Joshua J. Mark, “Silk Road,” World History, May 1, 2018, https://www.worldhistory.org/Silk_Road/.

[6]Morris Rossabi, “Central Asia: A Historical Overview,” Asia Society, accessed on 1 October, 2022, https://asiasociety.org/central-asia-historical-overview.

[7]China Through a Lens, “The Development of Western China,” accessed on 15 September, 2022, http://www.china.org.cn/english/features/38260.htm#:~:text=In%202000%20China%20started%20a%20develop-the-west%20campaign.%20The,made%20the%20western%20region%20a%20hot%20investment%20spot.

[8]Susana A. Thornton, “China in Central Asia: Is China Winning the ‘New Great Game?,’” Brookings Institution, June 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/FP_20200615_china_central_asia_thornton.pdf.

[9]Paul Goble, “Beijing Expanding Size and Role of Its ‘Private’ Military Companies in Central Asia,” Eurasia Daily Monitor 18, no. 115 (July 20, 2021), https://jamestown.org/program/beijing-expanding-size-and-role-of-its-private-military-companies-in-central-asia/.

[10]Temur Umarov, “China Looms Large in Central Asia,” Carnegie Moscow, March 30, 2020, https://carnegiemoscow.org/commentary/81402.

[11]Gazeta.uz, “Foto: Uchenija Natsgvardii Narodnoj militsii KItaja,” May 7, 2019, https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2019/05/07/gvardiya/.

[12]Vesti.kg, “Kyrgyzsko-kitajskije uchenija ‘Sodruzhesvo-2019’ proshli w Urumchi,” August 16, 2019, https://vesti.kg/politika/item/63704-kyrgyzsko-kitajskie-ucheniya-sotrudnichestvo-2019-proshli-v-urumchi-foto.html.

[13]China News, “专家谈中国全球战略:应东稳、北强、西进、南下” [Experts Talked About China’s Global Strategy: It Should Be Stable in the East, Strong in the North, Moving West, and Going South], December 18, 2012, https://www.chinanews.com.cn/mil/2012/12-18/4416116.shtml.

[14]IWEP, “Sotrudnishestvo gosudarstv Tsentralnoii Azii s Kitajem: problem I perspektivy strategicheskogo partnerstva,” September, 20, 2019, https://iwep.kz/#/posts/5d84b95ad02b6c51acde3600/.

[15]Sergey Sukhankin, “Tracking the Digital Component of the BRI in Central Asia, Part One: Exporting “Safe Cities” to Uzbekistan,” China Brief 21, no. 3 (February 11, 2021), https://jamestown.org/program/tracking-the-digital-component-of-the-bri-in-central-asia-part-one-exporting-safe-cities-to-uzbekistan/; Sergey Sukhankin, “Tracking the Digital Component of the BRI in Central Asia, Part Two: Developments in Kazakhstan,” China Brief 21, no. 9 (May 7, 2021), https://jamestown.org/program/tracking-the-digital-component-of-the-bri-in-central-asia-part-two-developments-in-kazakhstan/.

[16]Chinese State Council, “China-Central Asia Trade Grew by 100 Times Over 30 years,” January 18, 2022, http://english.www.gov.cn/statecouncil/ministries/202201/18/content_WS61e60de2c6d09c94e48a3cf9.html.

[17]Eurasian Research Institute, “Economic Cooperation Between Central Asia and China,” accessed on November 1, 2022, https://www.eurasian-research.org/publication/economic-cooperation-between-central-asia-and-china/.

[18]Almaz Kumenov, “China Promises More Investment at Central Asia Summit,” Eurasianet, January 26, 2022, https://eurasianet.org/china-promises-more-investment-at-central-asia-summit.

[19]Xinhua, “Backgrounder: Economic Corridors Under Belt and Road Initiative,” May 9, 2017, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-05/09/c_136268314.htm.

[20]Tashkent Times, “Shavkat Mirziyoyev Proposed to Declare the Year 2020 as the Year of Development of Science, Education and the Digital Economy,” January 24, 2020, https://tashkenttimes.uz/national/4899-shavkat-mirziyoyev-proposed-to-declare-the-year-2020-as-the-year-of-development-of-science-education-and-the-digital-economy.

[21]Nargiza Muratalieva, “Ruslan Izimov o strategii Kitaja w Tsentralnoii Azii: analiz novykh podhodov I trendov,” Central Asian Analytical Network, June 27, 2019, https://www.caa-network.org/archives/17410#_ftn1.

[22]Elizabeth Woods and Thomas Baker, “Public Opinion on China Waning in Central Asia,” The Diplomat, May 5, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/05/public-opinion-on-china-waning-in-central-asia/.

[23]Talgat Isakov, “Antikitajskii protest w Kazakhstane – analiz kluchevykh momentov proshedshih sobytii,” Polit-asia.kz, September 11, 2019, https://polit-asia.kz/antikitajskij-protest-v-kazahstane-analiz-klyuchevyh-momentov-proshedshih-sobytij/.

[24]Diapazon, “Podralis kitajskije I mestnyje rabochie,” 23 September, 2010, https://diapazon.kz/news/15788-podralis-kitajjskie-i-mestnye-rabochie.

[25]Kanat Altynbajev, “2019 stal godom uslienija antikitajskih nastrojenij w Kazakhstane,” January 17, 2020, https://central.asia-news.com/ru/articles/cnmi_ca/features/2020/01/17/feature-03.

[26]Adrian Zenz, “New Evidence for China’s Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang,” China Brief 18, no. 10 (May 15, 2018), https://jamestown.org/program/evidence-for-chinas-political-re-education-campaign-in-xinjiang/.

[27]OCCRP, “President Kirgizii o korrupcii na tamozhne: ‘Takih, kak Matraimov, byli sotni,’” December 25, 2019,

https://www.occrp.org/ru/daily/11359-2019-12-25-09-24-27.

[28]Sergey Sukhankin, “Tajik-Kyrgyz Border Clashes and Russia’s Limited Role: Is the Region on the Brink of Geopolitical Change?,” Eurasia Daily Monitor 18, no. 80 (May 19, 2021), https://jamestown.org/program/tajik-kyrgyz-border-clashes-and-russias-limited-role-is-the-region-on-the-brink-of-geopolitical-change/.

[29]Mollie Saltskog and Colin P. Clarke, “The Little-Known Security Gaps in China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” RAND Corporation, February 18, 2019, https://www.rand.org/blog/2019/02/the-little-known-security-gaps-in-chinas-belt-and-road.html.

[30]“’协作-2019’中塔联合反恐演练结束 参演兵力1200人” [“Cooperation-2019” China-Tajikistan Joint Anti-Terrorism Exercise Ended With 1,200 Troops Participating], August 16, 2019, https://www.sohu.com/a/334223602_428290

[31]Sergey Sukhankin, “Chinese Private Security Contractors: New Trends and Future Prospects,” China Brief 20, no. 9 (May 15, 2020), https://jamestown.org/program/chinese-private-security-contractors-new-trends-and-future-prospects/.

[32]Human Rights Watch, “Kazakhstan. Sobytija 2019 goda,” accessed 13 September, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/ru/world-report/2020/country-chapters/336554.

[33]Manshuk Asaulay, “Kitajskije investitsii: opasenija naselenija I interesy wlastej,” Radio Azattyk, September 9, 2019, https://rus.azattyq.org/a/kazakhstan-china-protests-roots-opinions/30154375.html.